J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2019;5:30-36.

|

http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh201953036 Received: 01 October 2019; Published on-line: 30 October 2019 Features of social and psychological adjustment in visually impaired adolescents O.I. Vlasova1, Dr Sc (Psychology), Prof.; V.I. Podshyvalkina2, Dr Sc (Psychology), Prof.; N.V. Rodina2, Dr Sc (Psychology), Prof.; K.L. Miliutina1, Dr Sc (Psychology), Assoc Prof.; A.M. Lovochkina1, Dr Sc (Psychology), Prof 1 Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv; Kyiv (Ukraine) 2 Mechnikov National University of Odesa; Odesa (Ukraine) E-mail: nvrodinaod@gmail.com TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Vlasova OI, Podshivalkina VI, Rodina NV, Miliutina KL, Liovochkina AM. Features of social and psychological adjustment in visually impaired adolescents. J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2019;5:30-36. http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh201953036

Background: While considering the issues of the socialization of visually impaired children, we feel it is important to note that the conditions under which they develop depend on adverse childhood experiences and whether they attend and/or live in a residential school that negatively affects adolescent’s social and psychological adaptability. The problem of research on the personality development in these children is that it is difficult to separate the secondary defect developing due to reduced efficiency of the visual system from the impact of a specific developmental setting. Depending on the severity of visual impairment and whether the parental family is problem free, in Ukraine, visually impaired children usually attend a residential school, a non-residential school for visually impaired children, or a mainstream school, and are raised in the respective developmental setting. This is why it is important to determine which of these settings is most appropriate for the personality development of a visually impaired child. Purpose: To identify the impact of socialization setting of residential school, non-residential school for visually impaired children, or mainstream school and adverse childhood experiences on the adaptability of visually impaired adolescents. Materials and Methods: Ninety-five visually impaired adolescents of 15 or 16 were included in this study. Of these, 32 adolescents attended a special residential school for visually impaired children and lived there, 30 attended this school but lived with their parental family, and 33 attended mainstream schools. The study was conducted with the use of the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Questionnaire as modified by one of the authors; the Rogers and Diamond Psychological Adaptation Inventory, Wasserman Social Frustration Inventory, Spielberger's State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults, and Multilevel Personal Adaptability Inventory (MLPAI). Results: Using the Rogers and Diamonds Inventory, we found significant differences (Kruskal Wallis test at the level of 0.05) in adaptability, self-perception, perception and emotional comfort between groups. In addition, trait anxiety was negatively correlated with adaptability (r= -0.755, p=0.000, Spielberger Inventory) in children attending and living at the residential school. There were negative correlations of health satisfaction and social frustration (as assessed by the Wasserman Inventory) with maladjustment, non-self-acceptance, emotional discomfort, self-control and escapism as accessed by the Rogers and Diamonds Inventory (all these correlations were significant at levels of 0.005 and 0.001). For the MLPAI, the level of orientation towards moral norms of society points to the role of family upbringing in the moral development of the child, and was correlated (r= 0.461 at the level of 0.01) with health satisfaction. For the modified ACE Questionnaire, all subjects reported a history of several (three to eight) hospitalizations, with the incidence and duration of hospitalizations depending on the eye disease and the potential for disease correction. Squared chi test found significant differences between groups. The level of adverse childhood experiences was positively correlated with anxiety (+0.652) and negatively correlated with emotional comfort (-0.746) and adaptability (-0.528), but no significant correlation was found with other indices. The presence of parents’ antisocial behavior worsened behavioral regulation (-0.697) and orientation towards moral norms of society (-0.586).

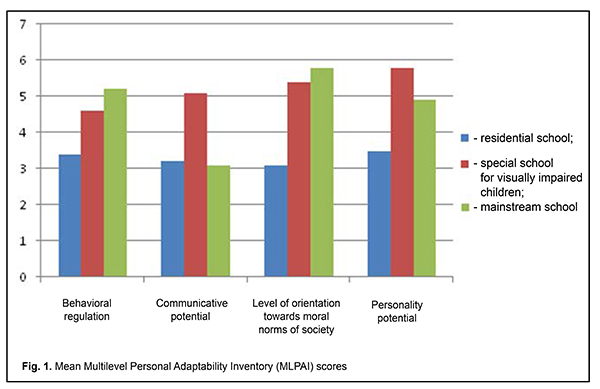

Introduction The problem of research on the personality development in visually impaired children is that it is difficult to separate the secondary defect developing due to reduced efficiency of the visual system from the impact of a specific developmental setting. Depending on the severity of visual impairment and whether the parental family is problem is problem free, in Ukraine, visually impaired children usually attend a residential school, a non-residential school for visually impaired children, or a mainstream school, and are raised in the respective developmental setting. This is why it is important to determine which of these settings is most appropriate for the personality development in a visually impaired child. It has been reported [1;2] that biological and social factors have an effect on the personality development of a visually impaired adolescent. In addition, psychosocial problems of visually impaired individuals do not disappear with childhood [3], and visually impaired adult individuals experience difficulties in initiating or maintaining an adequate family relationship. Therefore, little is known on the way in which adverse childhood experiences and residential school setting influence social and psychological adaptability of visually impaired adolescents. The purpose of this study was to identify the impact of socialization setting of residential school, non-residential school for visually impaired children, or mainstream school and adverse childhood experiences on the adaptability of visually impaired adolescents. Materials and Methods Ninety-five visually impaired adolescents of 15 or 16 were included in this study. Of these, 32 adolescents attended a special residential school for visually impaired children and lived there, 30 attended this school but lived with their parental family, and 33 attended mainstream schools. The study was conducted with the use of the Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Questionnaire as modified by Miliutina [4]. The original ACE Questionnaire [5] was adapted to the requirements of the current study due to the following reasons: (1) it contains only 10 questions, and any of these may be related to various types of violence, and, (2) it is targeted at individuals above 18 years of age, whereas our study involved individuals aged 15 or 16. In the modified ACE Questionnaire, different types of violent and adverse events are accounted for separately. Some additional questions are related to physical restraint school bullying, and history of severe disease requiring hospitalization. These changes were made taking into account the features of visually impaired adolescents. Our version of modified ACE Questionnaire is provided in the appendix of the paper. In addition, in the current study we used the Rogers and Diamond Psychological Adaptation Inventory [6], Wasserman Social Frustration Inventory [7], Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults [8], and Multilevel Personal Adaptability Inventory (MLPAI) [9]. Pupils from the residential school for visually impaired children, and mainstream school children with high myopia, retinal degeneration or glaucoma were included in the study. Results Using the Rogers and Diamond Psychological Adaptation Inventory, we found significant differences (Kruskal Wallis test, p ? 0.05) in adaptability, self-perception, perception and emotional comfort between groups. Adolescents attending a mainstream school or living with their parental family mostly demonstrated moderate adaptability and low to moderate emotional comfort and self-perception. Those attending and living at the residential school demonstrated moderate general adaptability, but low emotional comfort and perception. In addition, trait anxiety was negatively correlated with adaptability (r= - 0.755, p=0.000, Spielberger Inventory) in children attending and living at the residential school. There was, however, no Spearman correlation for the two other groups. Since adolescents attending a mainstream school or living with their parental family also had moderate to high trait anxiety (as assessed by the Spielberger Inventory), one may hypothesize that even high trait anxiety does not affect adaptability of adolescents to mainstream school. The above relationship was specific for visually impaired adolescents living at the residential school, but neither high anxiety, nor correlation between anxiety and any other characteristics was found in those attending, but not living at the residential school. The self-perception (as assessed by the Rogers and Diamond Inventory) showed that visually impaired adolescents found it difficult to accept their impairment. Self-perception was correlated with health satisfaction (Spearman correlation, r=0.548, p =0.001) in each of the study groups. One may hypothesize that an increase in self-perception will lead to an increase in appearance and health satisfaction. There were negative correlations of health satisfaction and social frustration (as assessed by the Wasserman Inventory) with maladjustment, non-self-acceptance, emotional discomfort, self-control and escapism as accessed by the Rogers and Diamonds Inventory (all these correlations were significant at levels of 0.005 or 0.001). Figure 1 presents the results for the MLPAI.

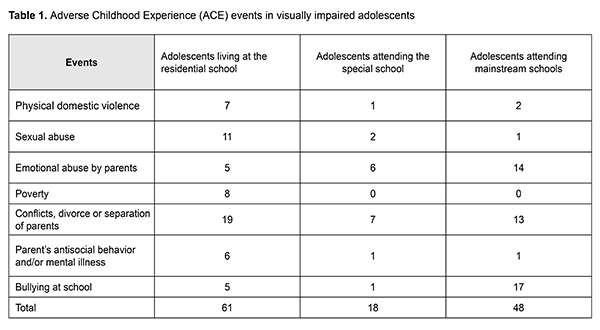

For the MLPAI, there was a significant difference (Mann Whitney, p ? 0.05) both in communicative potential and personality potential between children living at home and at the residential school. Communicative potential and personality potential in children living at the residential school or attending mainstream schools were significantly lower than in pupils attending the residential school but living with their parental family. In addition, it is noteworthy that the two groups socializing in problem-free parental families had almost the same orientation towards moral norms of society, which points to the role of family upbringing in the moral development of the child. This characteristic was found to correlate (Spearman correlation, r= 0.461 p ? 0.01) with health satisfaction in visually impaired adolescents. For the modified ACE Questionnaire, all subjects reported a history of several (three to eight) hospitalizations, with the incidence and duration of hospitalizations depending on the eye disease and the potential for disease correction. Other events were distributed unevenly among the three groups (Table 1).

Squared chi test found significant differences between groups. The level of adverse childhood experiences was positively correlated with anxiety (+0.652) and negatively correlated with emotional comfort (-0.746) and adaptability (-0.528), but no significant correlation was found with other indices. The presence of parents’ antisocial behavior worsened behavioral regulation (-0.697) and orientation towards moral norms of society (-0.586). Discussion Various authors, including Malkova [10] and others [2] discussed the features of social and psychological adjustment in visually impaired adolescents and noted that high trait anxiety and low emotional comfort are characteristic for adolescents who are blind or have low vision. A study by Romanova [12] aimed to identify psychological features of disabled adolescents and found that they overestimated their strength, potential, knowledge and position in society, i.e. had inappropriately high aspirations. Over- or underestimation of personal strength, ability and position in society are more frequently found in impaired subjects than in unimpaired subjects [6, 7, 13-15]. This is true of visually impaired adolescents. However, an unimpaired individual as well as an impaired one has a personal potential for adaptability, and may develop and implement his or her own life script [16]. A previous study by one of the authors [1] on socialization of visually impaired children under residential school conditions has demonstrated the efficiency of after school class and training activities for correcting low self-esteem and low adaptability in adolescents. Foreign authors [17] noted that the social setting in which personality development of visually impaired children takes place varies from culture to culture. In addition, a positive effect of sport activities on improvements in body esteem and self-esteem in visually impaired adolescents was investigated [18]. We conducted the study on the influence of development and education settings (a residential school, a non-residential school for visually impaired children, and a mainstream school) and relevant adverse childhood experiences on social and psychological adaptability of visually impaired adolescents to identify the features of accumulation of these experiences in and maladjustment of these adolescents. Maladjustment of visually impaired adolescents attending a mainstream school may be explained by the fact that after getting involved in an inclusive setting, they start feeling that they are unable to compete with their unimpaired classmates, they have sensorimotor impairments and secondary communication problems. In addition, they were in a difficult psychological situation primarily due to uneasy relations with peers and conflicts and misunderstanding with own parents. This creates stress load but is normal for adolescents. Those attending a specialized school for visually impaired children but living with their parental family demonstrated high scores regarding adaptability domain and its components, and felt comfortable both in the educational setting and at home. Maladjustment manifestations in visually impaired adolescents living under residential school conditions could be caused by the fact that they were mostly from low-income and socially disadvantaged families. We found support for our hypothesis that low adaptability and low level of orientation towards moral norms of society in visually impaired adolescents living under residential school conditions are associated with the features of their family socialization and not with visual impairment. These children were mostly from deprived families, with alcohol-dependant and mentally ill parents arguing with each other and using violence against their child. Elevated sexual abuse scores are attributed to sexual harassment both at home and at the residential school from older residents, but adolescents do not pay much attention to relationships with peers, and commonly do not suffer from bullying at school. We found that a portion of visually impaired adolescents were also negatively affected both by the residential school setting or mainstream school setting and by disadvantaged families, which did not allow exact identification of the factor resulting in poor social and psychological adjustment of adolescents. Severely visually impaired adolescents have difficulties in making contacts with the people around them, which was confirmed by their integral perception scores and total adaptation scores as accessed by the Rogers and Diamond Psychological Adaptation Inventory. Underestimation of personal strength, ability and position in society are more frequently found in visually impaired adolescents than in unimpaired subjects. Inability to make social relationships may result in increasing detachment from the people around them, contributing to inadequate perception of reality with formation of attitude to avoidance of contact with visually unimpaired individuals. Visually impaired adolescents are brought up at the residential school or special school under conditions of isolation from visually unimpaired peers, and, therefore, they have poor chances for communication with these peers. Although visually impaired adolescents attending mainstream schools do have good chances for communication with visually unimpaired individuals, they exhibited low communicative potential due to the secondary defect associated with intensive visual impairment. Conclusion There were significant differences in adaptability, self-perception, perception, emotional comfort, communicative potential and level of orientation towards moral norms of society between groups of visually impaired adolescents under various socialization conditions (i.e., attending a residential school, a non-residential school for visually impaired children, or a mainstream school). The features of accumulation of adverse childhood experiences and maladjustment were identified in these adolescents. Low adaptability and low level of orientation towards moral norms of society in visually impaired adolescents living under residential school conditions are associated with the features of their family socialization and not with visual impairment. The findings of this study demonstrate that living at home while attending a school for visually impaired children and are most appropriate for the personality development and social and psychological adjustment of visually impaired adolescents. Therefore, creating adequate conditions for visually impaired adolescents to attend special classes in mainstream schools would facilitate their optimal socialization and adjustment. References 1.Miliutina KL. [Impact of informal activities on socialization of visually impaired adolescents]. Nauka i osvita. 2016;(9):111-7. Ukrainian. 2.Shimgaieva AN. [Phenomenon of anxiety in visually impaired adolescents]. Abstract of Cand Sc (Psychology) Thesis]. Moscow: Institute for Correctional Pedagogics; 2007. Russian. 3.Retznik L, Wienholz S, Seidel А, Riedel-Heller S. Relationship Status: Single? Young Adults with Visual, Hearing, or Physical Disability and Their Experiences with Partnership and Sexuality. Sex Disabil. 2017 Jul. 4.Miliutina KL. [Empirical model of adult consequences of childhood experience]. In: [Maksimenko SD, Shevchenko NF, Tkalich MG, editors. Current psychology issues: Collection of science articles by authors from the National University of Zaporizhzhia and Kostiuk Institute of Psychology of the NAPS of Ukraine]. 2018;2(14):78-83. Ukrainian. 5.Kobasa SC, Maddi SR, Kahn S. Hardiness and health: a prospective study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1982 Jan;42(1):168-77. 6.Litvak AG. [Psychology of blindness and low-vision]. St Petersburg: Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia; 1998. Russian. 7.Vasserman LI, Iovlev BV, Berebin MA. [Methodology for psychological diagnosing the level of social frustration]. St Petersburg: Bekhterev Research Psychoneurological Institute; 2005. p.44-9. Russian. 8.Batarshev AV. [Major psychologic personality characteristics and personality self-determination: The Practical Book of Psychological Diagnosis]. St Petersburg: Rech; 2005. p.44-9. Russian. 9.DIa Raigorodskii, editor and compiler. [Practical Psychodiagnostics: Methodology and tests]. Samara: BAKHRAKH-M Publishing House; 2006. Russian. 10.Malkova TP. [Assessing the probability for successful social and psychological adjustment for visually impaired school graduates]. Pedagogika, psikhologiia teoriia i metodika obucheniia. 2002;(3):188-91. Russian. 11.Nikulina IN. [Developing self-appraisal in visually impaired school children]. Abstract of Cand Sc (Psychology) Thesis]. St Petersburg: Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia; 2006. Russian. 12.Romanova OL. [Experimantal psychological study of personality in physically handicapped patients]. Zh Nevrologii Psihiatrii im SS Korsakova. 1982;2(2):98. Russian. 13.Kriukova EV. [Developing a positive self concept in visually impaired adolescents]. Psikhologicheskiie i pedagogicheskiie nauki: Vserossiyskii zhurnal nauchnykh publikatsii. 2011 Apr:50-1. Russian. 14.Lemak MV, Petrische VE. [Methodological book for practicing psychologists: Diagnostic methodologies]. Uzhgorod: Vydavnytstvo Oleksandry Garkushi; 2011. p.15-23. Ukrainian. 15.Lipkova OI. [General and specific features of personality development in visually impaired adolescents]. [Abstract of Cand Sc (Psychology) Thesis]. Moscow: Lomonosov State University of Moscow; 2001. Russian. 16.Chepeleva NV. [Discursive practices in personality self-design]. Nauka I osvita. 2015;(10):5-11. Ukrainian. 17.Sacks SZ, Wolffe KE. Lifestyles of Adolescents with Visual Impairments: An Ethnographic Analysis. J Vis Imp Blind. 1998;92(1);9–17. 18.Anderson R, Warren N, RoseAnne Misajon R, Lee S. You need the more relaxed side, but you also need the adrenaline: promoting physical health as perceived by youth with vision impairment. Disabil Rehabil. 2019 Jan 22:1-8.

Appendix Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Questionnaire as modified by Miliutina Instruction. If yes, enter +. 1. Did an adult often or very often insult you or humiliate you? 2. Did an adult act in a way that made you afraid that you might be physically hurt? 3. Did an adult often push, grab, slap, or throw something at you? or Ever hit you so hard that you had bruises? 4. Have you ever been hospitalized for more than seven days for an injury or illness? 5. Did an adult or person at least 5 years older than you ever touch or fondle you in a sexual way? 6. Did an adult or person at least 5 years older than you ever have sex with you? 7. Did you often or very often feel that no one loved you or thought you were important or special? 8. Did you feel that your family didn’t look out for each other, feel close to each other, or support each other? 9. Did you often or very often feel that you didn’t have enough to eat and had to wear dirty clothes? 10. Did you often feel that your parents were too drunk or high to take care of you if you needed it? 11. Were your parents ever separated or divorced? 12. Was your mother or other family member often or very often pushed, grabbed, or slapped? 13. Was your mother or other family member ever threatened with a gun or knife by an adult? 14. Did you live with anyone who was a problem drinker or alcoholic or who used drugs? 15. Did a household member go to prison? 16. Was a household member mentally ill? 17. Did a household member attempt suicide? 18. Were you often or very often being punished by an adult by being locked in a room or tied up? 19. Were you often or very often being punished by an adult by being not talked to for hours? 20 Were you ever a victim of bullying or violence at school? Score 1 point for each Yes answer above. Add up “Yes” answers to get a total ACE score for each subject. While performing qualitative processing of ACE questionnaire results, the researcher should pay attention to whether an adverse childhood experience is physical abuse, psychological abuse, sexual abuse, bullying at school, etc. The authors certify that they have no conflicts of interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

|