J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2019;3:52-56.

|

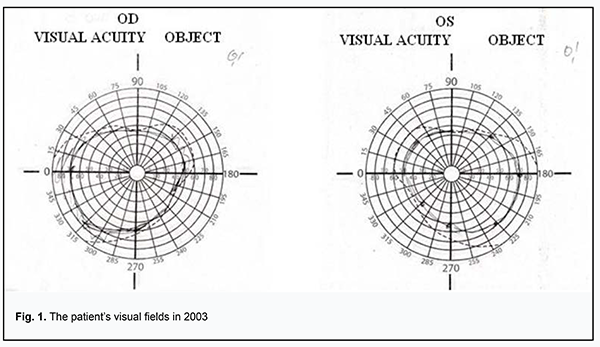

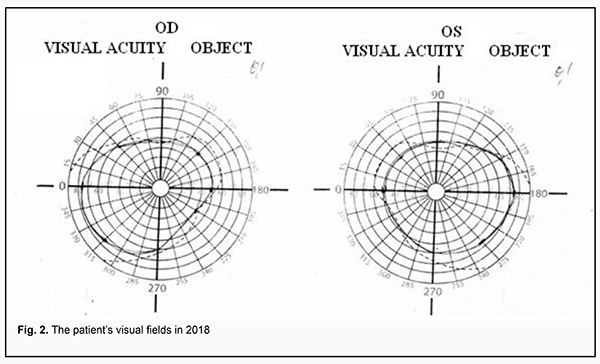

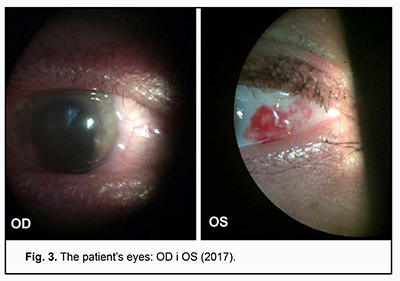

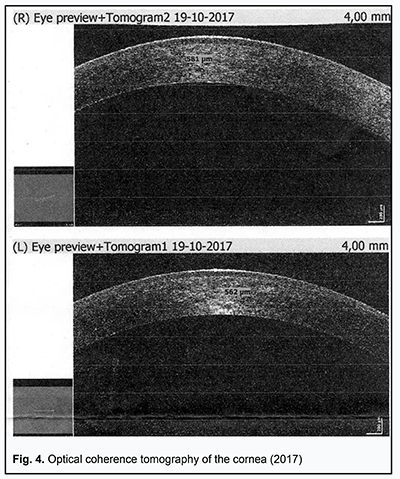

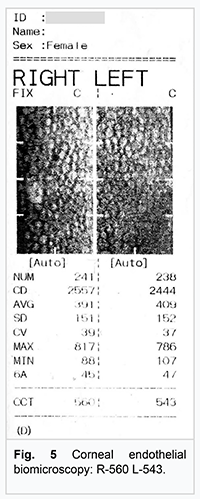

Received: 19 February 2019; Published on-line: 27 June 2019 http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh201935256 A Case Report of Kussmaul-Maier Disease O.O. Andrushkova, Cand Sc (Med); N.V. Malachkova, Cand Sc (Med); K.Iu. Grizhimalskaia, Cand Sc (Med); Ie.G. Manko, Student; T.M. Zhmud, Cand Sc (Med) Vinnitsa National Pirogov Memorial Medical University; Vinnitsa (Ukraine) E-mail: gtatyana@email.ua TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Andrushkova OO, Malachkova NV, Grizhimalskaia KIu, Manko IeG, Zhmud TM. A Case Report of Kussmaul-Maier Disease. J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2019;3:52-6. http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh201935256 Background: Kussmaul-Maier disease (also known as polyarteritis nodosa or PAN) is a systemic disorder characterized by destructive and proliferative changes in the walls of arteries (mainly muscular arteries and arterioles). Purpose: To present a case exemplifying the ocular manifestations of Kussmaul-Maier disease. Materials and Methods: The patient underwent visual acuity assessment, tonometry, and comprehensive eye examination. In addition, she underwent brain MRI and duplex sonography of the major arteries supplying the head. Results and conclusion: This case demonstrates the features of disease course and ophthalmologist’s tactics in the treatment of Kussmaul-Maier disease. Kussmaul-Maier disease has a recurrent course with long-lasting (as long as 11 years) periods of remission and favorable visual prognosis. Keywords: Kussmaul-Maier disease, periarteritis nodosa Kussmaul-Maier disease (also known as polyarteritis nodosa or PAN) is a systemic disorder characterized by destructive and proliferative changes in the walls of arteries (mainly muscular arteries and arterioles) due to a hypersensitivity response of the body (especially of the vascular system) to the influence of various factors [1-3]. Kussmaul and Maier gave the first complete description of the disease in 1866 and assigned the name “periarteritis nodosa” to it. It is a rare disease, with an estimated incidence of 1 per 100,000. Men are affected three times more often than women. The disease can affect individuals of any age, but the onset is more common between the ages of 40 and 60 years [4, 5]. To date, the etiology remains controversial. Studies have, however, demonstrated the major etiologic role of hypersensitivity of the body to various factors (infections including viruses, intoxication, administration of particular medications, exposure to cold, etc.) that lead to allergy with characteristic immune response to allergens. Hepatitis B infection is believed to be a risk factor for PAN. Others theorize that PAN development is affected by the cytomegalovirus, rubella, hepatitis C or Epstein-Barr virus. Familial PAN has been reported [6, 7]. Hyperergic reaction develops in response to etiologic factors, and involves a formation of immune complexes that are fixed in vessel walls, leading to autoimmune inflammation in the walls. These processes are accompanied by production of blood coagulation factors and thrombus formation factors by the endothelium of damaged vessels [8, 9]. There is histological evidence of inflammatory cell infiltration and fibrinoid necrosis in the adventitia, media and endothelium. In the active disease (especially in the early active disease), neutrophils are predominant cells, and numerous nucleus fragments from disrupted cells may be seen. In the late disease, mononuclear cells are seen in infiltrates, and moderate numbers of eosinophils may be present. Isolated giant cells are rare. Once the inflammation at a particular vessel site has subsided, the inflammatory infiltrate vanishes, and the inflammatory tissue formed in the primary focus (especially in the subendothalial layer) is replaced by fibrous tissue, with rupture of the internal elastic membrane. A patient with PAN exhibits arterial lesions varying in size and degree of severity. Actually, large perivascular nodes (aneurysms or inflammatory infiltrates) develop rarely. Severe arterial wall damage results in thrombus and aneurysm formation, leading to frequent infarctions and hemorrhages typical for PAN [10-12]. Clinical picture The disease begins with general symptoms of persistent fever, progressive weight loss, and muscle and joint pain. The five most common syndromes are vascular lesions of the kidney, abdominal cavity organs and tissue, heart, lungs and peripheral nervous system. Ocular symptoms should be given special attention. Fundus examination frequently reveals inflammatory changes affecting fundus arteries and degenerative alterations due to increased vascular permeability, including that for plasma components. Arteritis underlies scleritis, intraocular hemorrhage, choroiditis, and central retinal artery occlusion, leading to loss of vision. Typically, arterial hypertension (mostly, of a stable and persistent type, sometimes, malignant) develops, which results in severe retinopathy, thickened fundus vessels and aneurysms [13, 14]. Treatment Corticosteroids are most efficacious in early disease. Prednisolone is administered at a high dose of 60-100 mg (and sometimes as high as up to 300 mg) daily for 3-4 days. The hormone treatment is gradually tapered as patient improves, and withdrawn once clinical remission is achieved. Two to three hormone therapy cycles (300 mg per cycle) a year are administered for prophylaxis. A patient may require maintenance therapy for months and even years. Salicylate (aspirin at a daily dose of 3 g) or pyrazolone (primarily, phenylbutazone, 0.15 g thrice a day) is administered once the steroids have been withdrawn. In these cases, a white blood cell count should be performed at regular intervals during therapy. Cyclophosphamide or azathioprine is administered at a dose of 50 mg four times a day for 2.5-3 months. In addition, vitamins (especially B1 and B12) are necessary when the nervous system is affected, and therapeutic exercises, massage and hydrotherapeutic procedures are indicated [1, 2]. Prognosis PAN lethality is high in severe complications involving the internal organs. Chronic PAN patients become incapacitated due to peripheral or central paralysis, heart or lung lesion, etc. If early diagnosed and properly treated, the disease has a good prognosis for complete recovery or long-lasting remission. Remission or arrest of progress is achieved in 50 per cent of cases with PAN [1, 2, 4]. The purpose was to present a case exemplifying the ocular manifestations of Kussmaul-Maier disease. Materials and Methods Ms S, a 63-year-old woman, presented at the Ophthalmology Department of the Pirogov Clinical Hospital of Vinnytsia with a sudden loss of vision in the right eye. She had a ten year history of systemic vasculitis (periarteritis nodosa). Her medical history was also remarkable for congenital heart disease, ventricular septal defect with mitral insufficiency, and chronic cerebral circulation disorder. In 2003, she had bacterial endocarditis with arrhythmia, atrial fibrillation paroxysm and pneumonitis. The patient underwent general clinical tests, visual acuity assessment, tonometry, ophthalmoscopy, biomicroscopy, and perimetry. In addition, she was referred to hematologist, rheumatologist, and neurologist, and underwent brain MRI and duplex sonography of the major arteries supplying the head. Results of observation The patient presented with a complaint of sudden vision loss in 2003. The IOP normalized after treatment with a hypotensive agent. She stopped after taking the agent topically for 4 months, and did not come to the ophthalmologist with complaints until 2018. In 2003, she had bacterial endocarditis with paroxysmal arrhythmia, pneumonitis and transitory hematuria. Ms S, a 63-year-old woman, presented at the Ophthalmology Department of the Pirogov Clinical Hospital of Vinnytsia with a sudden loss of vision in the right eye. She had a long history of systemic vasculitis. On examination, general condition was satisfactory, her height was 158 cm and weight 40 kg, and she was alert in her bed. In addition, there were isolated hemorrhagic spots on the skin, and lung auscultation revealed vesicular respiration. Her heart rate was 82 bpm, her blood pressure was 90/70 mmHg, and auscultation showed a coarse, systolic murmur. Abdomen was painless and soft on palpation. Status oculorum OD: The VA OD was counting fingers near face and OD intraocular pressure (IOP) was 30 mm Hg. No periorbital lesions were present, and the palpebral fissure width was normal. The bulbar conjunctival veins were dilated and tortuous. There was a horizontal strip-shaped corneal edema. The anterior chamber was moderately deep, and was filled with clear aqueous humor. There was a congenital iris coloboma at 6 o’clock. No fundus reflex was visible. OS: The uncorrected VA was 0.5 OS, the best-corrected VA OS was 0.90 with 1.75 D sph, and OS IOP was 22 mm Hg. No periorbital lesions were present, and the palpebral fissure width was normal. There was hemorrhage in the external portion of the bulbar conjunctiva. The cornea was clear; the anterior chamber was moderately deep, and was filled with clear aqueous humor. There was a congenital iris coloboma at 6 o’clock. The fundus was unremarkable. Findings of auxiliary clinical examinations: Complete blood count and urine examination were normal. EEG findings: the rhythm was sinus; heart rate, 72/min; severe right axis deviation; left and right atrial hypertrophy; right ventricular hypertrophy and systolic overload of the right ventricle; left posterior hemiblock; and marked muscular changes. Findings of duplex sonography of the major arteries supplying the head: brachiocephalic trunk, subclavian arteries, common carotid artery, and internal carotid artery were passable. The course was straight line, and arterial walls were dense and not thickened. Spectral characteristics were within the normal range, whereas the blood flow velocity was reduced. Opinion formulated based on ultrasonography: ultrasonographic evidence of a diffuse atherosclerotic process; the blood flow in both vertebral arteries was reduced and right venous outflow was obstructed. Brain MRI findings: Axial, saggital and frontal brain MRI images demonstrated neither displacement of midline structures, nor enlargement of the ventricular system or changes in the chiasm and sellar region. In the presence of marked focal changes, there were hematic cysts in the right parietal lobe, and no changes in craniovertebral ligaments, orbital or paranasal sinuses. Convex subarachnoid spaces were non-uniformly expanded. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) demonstrated marked non-uniformly spastic distal branch of the medial cerebral artery and posterior cerebral artery. Opinion formulated based on MRI and MRA: hematic cysts are still present in the right parietal lobe in the presence of atrophic focal changes. Therapist’s opinion: hemorrhagic vasculitis in unstable remission; residual effects of transient ischemic attack (TIA) not associated with vasculitis; and congenital heart disease (ventricular septal defect). Neurologist’s opinion: cerebral vasculitis (residual effects in the form of pyramidal insufficiency). Hematologist’s opinion: secondary erythrocytosis. The following treatment regimen was agreed with the consulting specialists and included indirect anticoagulants, anti-ischemic agents, anti-inflammatory agents, and circulation enhancers: Diclofenac Sodium, i.m., once-daily for 5 days; Actovegin, i.v., once-daily for 10 days; Aethacizinum, 50 mg, 3 times a day; Rhythmocor, 1 capsule, 4 times a day; Magnicor, 75 mg, once-daily in the evening; Preductal MR, 1 capsule, 2 times a day; and Sildenafil, 6.25 mg, 3 times a day. In addition, topical treatment included Oftan® Timolol 0.5%, 1 drop in the right eye, 2 times a day; Diacarb (acetazolamid), 1 tablet; and dexamethasone 0.1%, 2 drops, 4 times a day. In 3-4 hours, visual acuity improved to 0.3-0.4. The next day, the uncorrected VA was 0.6 OD, the best-corrected VA OD was 0.8-0.9 with 0.75 D sph, and OD IOP was 20 mm Hg. The cornea was clear; the anterior chamber was moderately deep, and was filled with clear aqueous humor. There was a congenital iris coloboma at 6 o’clock. Rheumatologist’s opinion was sought once again. In the reported case of Kussmaul-Maier disease (periarteritis nodosa), the patient was found to have a temporary loss of vision (once 5-6 years) with raised IOP, corneal edema, dilated and tortuous bulbar conjunctival veins in the right eye and hemorrhage in the external portion of the bulbar conjunctiva in the left eye. Following treatment with local hormone therapy and topical hypotensive agents, there was a restoration of vision within 48-72 hours. Further observation of the patient during 6 months did not find raised IOP or changes in visual acuity and visual fields after withdrawal of hypotensive agents. Therefore, it may be concluded that Kussmaul-Maier disease has a recurrent course with long-lasting (as long as 11 years) periods of remission and favorable visual prognosis.

References 1.Kazimirko VK, Kovalenko VN. [Rheumatology tutorial for physicians: Answers and questions]. Donetsk: Zaslavskii Publishing House; 2009. Russian. 2.Nasonov EL, Baranov AA, Shilkina NP. [Vasculitides and vasculopathy]. Iaroslavl:Verkhniaia Volga; 1999. Russian. 3.Ramos F, Figueira R, Fonseca JE, et al. [Juvenile cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa associated with streptococcal infection]. Acta Reumatol Port. 2006 Jan-Mar;31(1):83-8. Portuguese. 4.Semenkova EN. [Systemic vasculitides]. Meditsina: Moscow; 1999. Russian. 5.Naumann-Bartsch N, Stachel D, Morhart P, et al. Childhood polyarteritis nodosa in autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome. Pediatrics. 2010 Jan;125(1):e169-73. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1999. 6.Skripchenko NV, Trofimova TN, Iegorova ES. [Infectious vasculitides: the role in the organ pathology]. Zhurnal infektologii. 2010;2(1):7-17. Russian. 7.Mason JC, Cowie MR, Davies KA, et al. Familial polyarteritis nodosa. Arthritis Rheum. 1994 Aug;37(8):1249-53. 8.Conri C, Mestre C, Constans J, Vital C. [Periarteritis nodosa-type vasculitis and infection with human immunodeficiency virus]. 1991 Jan-Feb;12(1):47-51. French. 9.Fink CW. The role of the streptococcus in poststreptococcal reactive arthritis and childhood polyarteritis nodosa. J Rheumatol Suppl. 1991 Apr;29:14-20. 10.Frey FJ. [Polyarteritis nodosa, a vanishing vasculitis since its main cause has been identified]. Ther Umsch. 2008 May;65(5):247-51. doi: 10.1024/0040-5930.65.5.247. Review. German. 11.Hogan SL, Satterly KK, Dooley MA, et al. Silica exposure in anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody-associated glomerulonephritis and lupus nephritis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2001 Jan;12(1):134-42. 12.Jennette JC, Falk RJ, Andrassy K, et al. Nomenclature of systemic vasculitides. Proposal of an international consensus conference. Arthritis Rheum. 1994 Feb; 37(2):187-92. 13.Stratta P, Messuerotti A, Canavese C, et al. The role of metals in autoimmune vasculitis: Epidemiological and pathogenic study. Sci Total Environ. 2001 Apr 10;270(1-3):179-90. 14.Tonnelier JM, Ansart S, Tilly-Gentric A, Pennec YL. Juvenile relapsing periarteritis nodosa and streptococcal infection. Joint Bone Spine. 2000;67(4):346-8. 15.Libman BS, Quismorio FP, Stimmler MM. Polyarteritis nodosa-like vasculitis in human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Rheumatol. 1995 Feb;22(2):351-5. The authors certify that they have no conflicts of interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

|