J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2019;4:13-17.

|

http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh201941317 Prevalence of and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in areas differing in local access to endocrinologic care I.J. Aliyeva, Y.J. Abdiyeva National Centre of Ophthalmology named after Acad. Zarifa Aliyeva; Baku (Azerbaijan) TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Aliyeva IJ, Abdiyeva YJ. Prevalence of and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in areas differing in local access to endocrinologic care. J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2019;4:13-17. http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh201941317

Purpose: To investigate the prevalence of and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in areas differing in access to endocrinologic care. Materials and Methods: The study was conducted in the Ganja-Gazakh economic region, whose administrative units differ from each other with respect to access to endocrinologic care and prevalence of type 1 diabetes mellitus and type 2 diabetes mellitus. In order to determine actual prevalence of diabetic retinopathy across the region, 479 diabetics underwent a routine examination. Results: Diabetic retinopathy was found in 28.8±2.1% (95% CI, 24.6%–33.0%) of patients with diabetes mellitus. It was found substantially less frequently in diabetics from the city of Ganja than in those from rural settlements with no access to endocrinologic care at the local level. Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy was the most common form of the disease (50.0±4.3%), followed by pre-proliferative and proliferative forms (34.1% and 15.9%, respectively). Pre-proliferative and proliferative forms were 2.8 times and 2.2 times, respectively, more common in the group of patients with no access to endocrinology service at the area of patient residence. Conclusion: The difference in local access to endocrinologic care among administrative units of the region is associated with the difference in risk for and late detection of diabetic retinopathy. Gender, type of diabetes, presence of complications, duration of diabetes mellitus, and treatment regimens are important risk factors for the development of diabetic retinopathy. Keywords: diabetic retinopathy, prevalence, risk factors

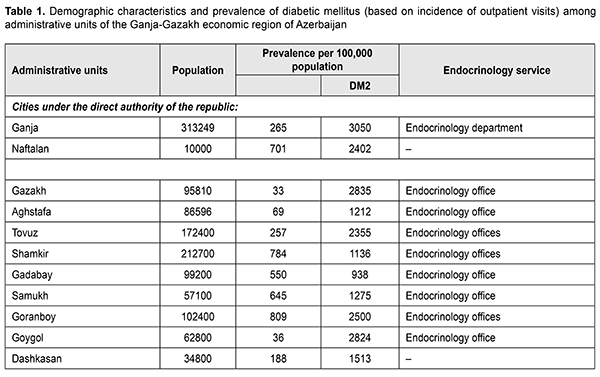

Introduction Diabetic retinopathy is a major cause of blindness in developed countries [1–16]. Although the pathogenesis of the disease is well described, current prevention measures are inadequate. Risk factors for diabetic retinopathy include duration of diabetes, glycemic control, inadequate treatment, hypertension, etc. Some of these factors are controllable and depend on the tactics and strategy of national healthcare services. It is from this circumstance that differences in prevalence of diabetic retinopathy across regions to some extent result [2, 3, 13-16]. The Diabetes Register operates in Azerbaijan, and, for the present, covers diabetics registered in the capital of the country; endocrinologic care is significantly less accessible to diabetics of the regions than to those of the capital. That is why we tried to assess the prevalence of and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in areas differing in access to endocrinologic care. The purpose of the study was to investigate the prevalence of and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in areas differing in access to endocrinologic care. Materials and Methods The study was conducted in the Ganja-Gazakh economic region, whose administrative units differ from each other with respect to access to endocrinologic care and prevalence of type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM1) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2). Table 1 presents demographic characteristics, prevalence of DM1 and DM2, and types of endocrinology service for various administrative units of the region. A well-developed in- and out-patient endocrinology service operates in Ganja, a city with a population of more than 300,000. Such towns as Naftalan and Dashkasan do not have an endocrinology service, and local diabetics are provided with care at the local level by general practitioners and at the regional level by endocrinologists. Rayon centers in rayons under the direct authority of the republic do have endocrinologists. While patients from a rayon center have access to endocrinologic care at the local level, those from rural settlements do not and are attached to an endocrinologist from this rayon center. It should be noted that there the prevalence of DM1 and that of DM2 varied widely among administrative units, ranging from 33 0/0000 to 809 0/0000 and from 9380/0000 to 3,050 0/0000, respectively.

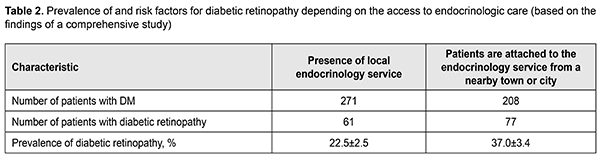

In order to determine actual prevalence of diabetic retinopathy across the region, a mobile ophthalmologist team from the Z. Aliyeva National Ophthalmology Center examined 479 diabetics, including 271 in the city of Ganja, where endocrinologic care is provided at the local level, and 208 in rural settlements and small towns, where there is no access to endocrinologic care at the local level. Patients underwent a routine examination including visual acuity assessment, perimetry, biomicroscopy, gonioscopy, tonometry, ophthalmoscopy and retinal tomography. In addition, if indicated, they underwent fluorescein angiography, fundus autofluorescence, spectral optic coherence tomography, etc. Data on diabetes duration, comorbidities, and treatment regimens was collected. Statistical analyses were conducted based on qualitative data analysis methods [17]. Results Table 2 presents data on the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among diabetics for those who have access to endocrinologic care at the local level and those who are attached to an endocrinologist from a nearby town or city.

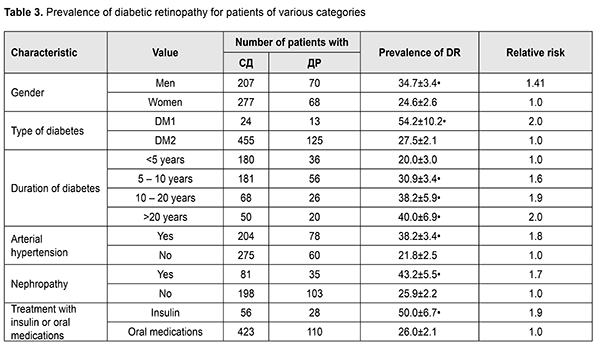

Obviously, inadequate access to endocrinologic care at the local level for patients with DM was associated with a high risk of diabetic retinopathy. Diabetic retinopathy was found in 28.8±2.1% (95% CI, 24.6%–33.0%) of patients with DM. It was found in 22.5±2.5% (95% CI, 17.5%–27.5.0%) of diabetics from Ganja, which was substantially less frequently than in those from rural settlements (37.0±3.4%, 95% CI, 30.2%–43.8%) with no access to endocrinologic care at the local level. Table 3 presents data on the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among diabetics depending on various patient characteristics.

The disorder was found substantially more frequently in men than in women (34.7±3.4% vs 24.6±2.6%), with a relative risk of 1.41 and attributable risk of 10.1%. DM1 was significantly more commonly complicated by diabetic retinopathy (54.2±10.2%) as compared to DM2. In addition, as compared to DM2 (27.5±2.1%), the risk of developing diabetic retinopathy was high (relative risk, 2.0; attributable risk, 26.7%). The risk of developing diabetic retinopathy linearly increased with an increase in the duration of diabetes, an important risk factor (20.0±3.0; 30.9±3.4; 38.2±5.9 and 40.0±6.9% for a duration of <5 years, 5 – 10 years, 10 – 20 years, and ?20 years). In the presence of arterial hypertension or nephropathy, diabetes mellitus was significantly more commonly complicated by diabetic retinopathy (38.2±3.8% and 43.2±5.5%, respectively). Diabetics treated with insulin exhibited diabetic retinopathy more frequently compared with those treated with oral medications (50.0±6.7% and 26.0±2.1%, respectively). Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy was found to be the most common form of the disease (50.0±4.3%), followed by pre-proliferative and proliferative forms (34.1% and 15.9%, respectively). Table 4 presents the data related to the distribution of clinical forms of diabetic retinopathy among patients from areas varying in access to endocrinologic care. The absence of endocrinology service directly at the areas of patient residence (towns and rural settlements) was associated with the dominance of pre-proliferative and proliferative forms in patients of the area. There were significant differences in the prevalence of individual clinical forms forms of diabetic retinopathy among patients from areas varying in access to endocrinologic care (Table 4). Pre-proliferative and proliferative forms were 2.8 times and 2.2 times, respectively, more common in the group of patients with no access to endocrinology service at the area of patient residence. Discussion The reported prevalence of diabetic retinopathy varies among studies [1 – 16] due to objective and subjective factors (characteristics of the diabetic patient population, quality of treatment programs, diagnostics of diabetic retinopathy, etc). The prevalence of diabetic retinopathy (28.9±2.1%; 95% CI, 24.6–33.0%) found by the mobile ophthalmologist team from the Z. Aliyeva National Ophthalmology Center in the region is close to that reported by studies from a number of countries [2 – 5]. Although, in general, our study did not show an abnormally high prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in the examined population, of note is a significant difference in the prevalence of the disease among areas differing in local access to endocrinologic care. The diabetics provided with endocrinologic care not at their residence areas but at nearby towns are limited in their chance for adequate treatment and medical supervision. That is why diabetics from rural settlements have an increased risk of developing diabetic retinopathy, especially severe forms of diabetic retinopathy. The odds for detection of pre-proliferative and proliferative forms of diabetic retinopathy were 2.2 times and 1.8 times greater for diabetics from settlements attached to an endocrinologist from a nearby town or city. Our data on risk factors for diabetic retinopathy are generally in agreement with findings from other studies [1 – 16], and some difference in relative risk is possibly due to the difference in methodology for computation of risk parameters. Conclusion First, the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy among diabetics from the Ganja-Gazakh economic region of Azerbaijan is 28.8±2.1% (95% CI, 24.6%–33.0%). Second, the difference in local access to endocrinologic care among administrative units of the region is associated with the difference in risk for and late detection of diabetic retinopathy. Finally, gender, type of diabetes, presence of complications and duration of diabetes mellitus, and treatment regimens are important risk factors for the development of diabetic retinopathy. References 1.Thapa R, Bajimaya S, Raundyal G, et al. Population awareness of diabetic eye disease and age related macular degeneration in Nepal: the Bhaktapur Retina Study. BMC Oftalmology. 2015 Dec 29;15:188. 2.Giloyan A., Harutyunyan T., Petrosyan V. The prevalence of and major risk factors associated with diabetic retinopathy in Gegharkunik province of Armenia: cross-sectional study. BMC Oftalmology. 2015 Apr 30;15:46. 3.Acan D, Calan M, Er d, et al. The prevalence and systemic risk factors of diabetic macular edema: a cross-sectional study from Turkey. BMC Oftalmology. 2018 Apr 12;18(1):91. 4.Bertelsen G, Peto T, Lindekleiv H, Schirmer H, et al. Troms? eye study: prevalence and risk factors of diabetic retinopathy. Acta Ophthalmol. 2013 Dec;91(8):716-21. 5.Jee D, Lee WK, Kang S. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy: the Korea National Health and nutrition examination survey 2008–2011. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013 Oct 17;54(10):6827-33. 6.Zheng Y, Lamoureux EL, Lavanya R, Wu R, Ikram MK. Prevalence and risk factors of diabetic retinopathy in migrant Indians in an urbanized society in Asia: the Singapore Indian eye study. Ophthalmology. 2012 Oct;119(10):2119-24. 7.Dehghan MH, Katibeh M, Ahmadieh H, Nourinia R, Yaseri M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in the 40 to 80 year-old population in Yazd, Iran: the Yazd eye study. J Diabetes. 2015 Jan;7(1):139-41. 8.Thapa R, Joshi DM, Rizyal A, Maharjan N, Joshi RD. Prevalence, risk factors and awareness of diabetic retinopathy among admitted diabetic patients at a tertiary level hospital in Kathmandu. Nepal J Ophthalmol. 2014 Jan;6(11). 9.Kahloun R, Jelliti B, Zaouali S, Attia S, Ben Yahia S, Khairallah M. Prevalence and causes of visual impairment in diabetic patients in Tunisia, North Africa. Eye (Lond). 2014 Aug;28(8):986-91. 10.Mathenge W, Bastawrous A, Peto T, Leung I, Yorston D, Foster A, Kuper H. Prevalence and correlates of diabetic retinopathy in a population based survey of older people in Nakuru, Kenya. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2014 Jun;21(3):169-77. 11.Sharew G, Ilako DR, Kimani K, Gelaw Y. Prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in Jimma University Hospital, Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2013 Apr;51(2):105-13. 12.Kaidonis G, Mills RA, Landers J, Lake SR, Burdon KP, Craig JE. Review of the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy in indigenous Australians. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2014 Dec;42(9):875-82. 13.Zhu M, Tong X, Zhao R, et al. Prevalence and associated risk factors of undercorrected refractive errors cross among people with diabetes in Shanghai. BMC Oftalmology. 2017 Nov 28;17(1):220. 14.Balashevich LI, Izmailov AS, editors. [Diabetic ophthalmopathy]. S Petersburg: Chelovek; 2012. p.137-42. Russian. 15.Rykov SA, Parkhonmenko OG, Parkhonmenko EG. [Improved method of fundus photography for screening of diabetic retinopathy and maculopathy with the use of ?Phone]. Oftalmol Zh. 2015;1:91-5. Russian. 16.Vorobieva IV, Merkushenkova DA. [Diabetic retinopathy in type two diabetic patients: Epidemiology and modern view on the pathogenesis. Review]. Ophthalmology in Russia. 2012;9(4):18-21. Russian. 17.Glantz S. [Medical biological statistics]. Transl. from English. Moscow: Praktika; 1998. Russian. The authors certify that they have no conflicts of interest in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

|