J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2022;3:65-73.

|

http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh202236573 Received: 26.04.2022; Accepted: 26.06.2022; Published on-line 15.06.2022 Developing a scale for assessing coping behavior in situations of danger N. V. Rodina 1, O. Iu. Dotsenko 1, A. V. Kernas 2, L. P. Pereviazko 1, L. K. Vornikova 1 1 Odessa I.I.Mechnikov National University; Odesa (Ukraine) 2 Odessa National Maritime University; Odesa (Ukraine) TO CITE THIS ARTICLE:Rodina NV, Dotsenko OIu, Kernas AV, Pereviazko LP, Vornikova LK. Developing a scale for assessing coping behavior in situations of danger. J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2022;3:65-73. http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh202236573

Background: The paper is focused on developing a psychodiagnostic tool for assessing coping behavior in situations of danger. Studies of coping behavior became increasingly important with the beginning of the Russian invasion in Ukraine on February 24, 2022. The version developed may become a reliable auxiliary tool for assessing the adaptive capacity of the personality, which is believed to be promising and of increasing importance for further studies. Purpose: To develop a psychodiagnostic tool for assessing coping behavior in danger situations to improve the adaptive capacity of the personality. Material and Methods: The study sample was composed of 311 responders (165 men and 146 women; mean age, 33.7 years). The study was conducted with the use of the seven-factor model of the Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WOCQ) as modified by Rodina. R-Studio software (version 1.4.1717) was used for statistical analyses of the questionnaire which included exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis, structural equation modeling, scale reliability analysis, correlation analysis and descriptive statistic analysis. Results: The Ukrainian-language five-factor model of the Scale for Assessing Coping Behavior in Situations of Danger developed includes the following subscales: Acceptance and Passive Reliance on Support, Acceptance and Passive Pessimism, Acceptance and Passive Optimism, Acceptance and Active Fighting, and Non-Acceptance and Dissociation. Application of the method for assessing coping behavior in situations of danger is promising and of increasing importance for further studies in order to improve the adaptive capacity of the personality. Keywords: coping behavior, personality, stress reactions, situation of danger, adaptive capacity, health care workers, patients with eye disease

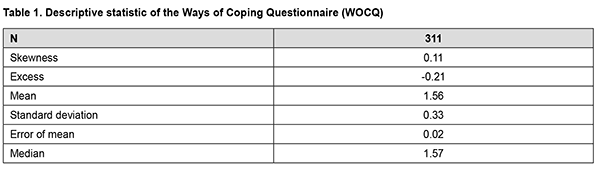

Problem setting With the beginning of the Russian invasion in Ukraine on February 24, 2022, it became increasingly important to develop a psychodiagnostic tool for assessing (a) coping behavior in situations of danger and (b) individual ways of coping with stressful, crisis, or life-threatening situations. The organization of psychological care in eye care practice entails an improvement in eye care workers’ and eye care patients’ knowledge of coping behavior in order to improve their adaptive capacity in situations of danger. This paper continues the series [1, 2, 3] on developing psychodiagnostic instruments for detecting stress reactions [1] and interrole conflicts [2] for eye-care workers, detecting adverse childhood experiences [3] as well as making these instruments psychometrically adapted to social and cultural realities of the Ukrainian professional environment. The tools proposed can be used as auxiliary tools to improve the adaptive capacity of eye care workers as well as patients with eye disease. McKinley and colleagues [4] aimed to assess resilience, professional quality of life and coping mechanisms in UK doctors. They found that the most frequently reported coping mechanism was the maladaptive strategy of self-distraction and believe that ensuring the psychological well-being of National Health Service doctors should be seen as a matter of national importance. Anil and Garip [5] pointed that patients with eye disease should develop adaptive coping strategies to manage their condition and supposed that diminishing disengaging coping strategies should be prioritized over developing engaging coping strategies to positively influence vision-related quality of life and emotional health [5]. We have previously [1] found that, among Ukrainian ophthalmologists, cognitive reactions to stressors (namely, stress assessment and coping) were more common than physiological, emotional, and behavioral reactions to stressors. Therefore, developing a scale for assessing coping behavior in situations of danger is believed to be promising and of increasing importance for further studies. Folkman and Lazarus developed the Ways of Coping Checklist Questionnaire (WCC) in 1980 [6]. The Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WOCQ) (1988) is a revised questionnaire derived from the original WCC [7]. The WOCQ has been translated into more than 20 languages and adapted for the use in different cultures and settings, and is one of the most well-known and commonly used copying assessment tools. In 2003, Khairova published the Russian-language version of the questionnaire, which was used in some studies by post-Soviet researchers [9]. In 2010 and 2014, Rodina developed Russian-language versions of the WOCQ, a seven-factor model (for emergency situations) and an eight-factor model (for self-actualization situations) [8, 10]. Recently, the WOСQ has been translated into Ukrainian and modified into a five-factor model which is based on the fight, flight or freeze response construct and measures an individual’s coping behavior in danger situations. Therefore, the purpose of this paper was to develop a psychodiagnostic tool for assessing coping behavior in situations of danger in order to improve the adaptive capacity of the personality. Material and Methods The study sample was composed of 311 responders (165 men and 146 women; mean age, 33.7 years). It is important that the data collection for modifying the questionnaire was conducted shortly after Russia launched an invasion of Ukraine on February, 24, 2022. A seven-factor model of the WOSQ for emergency situations developed by Rodina was used as a basis. R-Studio software (version 1.4.1717) was used for statistical analyses and to develop a new modified five-factor model of the questionnaire. The new version was named the Scale for Assessing Coping Behavior in Situations of Danger. The new construct is composed of the five subscales, Acceptance and Passive Reliance on Support, Acceptance and Passive Pessimism, Acceptance and Passive Optimism, Acceptance and Active Fighting, and Non-Acceptance and Dissociation, with the meanings of these subscales interpreted below. The responses are rated on a 4-point Likert scale, where 0 = Did not apply to me at all, 1 = Applied to me to some degree, or some of the time, 2 = Applied to me to a considerable degree or a good part of time, and 3 = Applied to me very much or most of the time. Criterion validity analysis was conducted using the Szondi Picture Selection Test [11] and the eight-factor model of the WOCQ for self-actualization situations as modified by Rodina [10]. Results Descriptive statistic analysis The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for normality. The null hypothesis was rejected in favor of the alternative hypothesis, there was a normal distribution of the data (р = 0.13). The mean value was practically equal to the median of the sample (Table 1), and the distribution was slightly platykurtic.

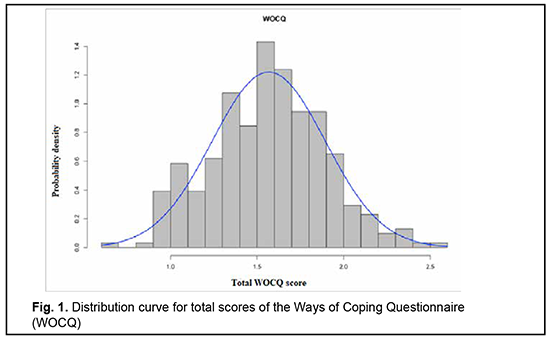

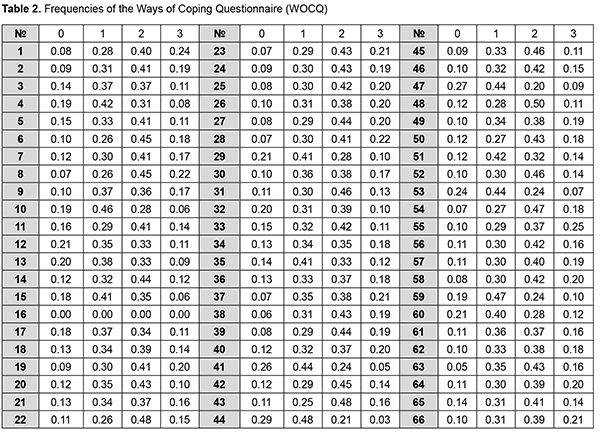

Fig. 1 shows the histogram of the distribution of total questionnaire scores, with a slight shift to the left in distribution demonstrating a decrease in the examined parameter. Performing questionnaire analysis requires reviewing and interpreting the frequency table (Table 2); this portion of the analysis is easy to perform and important for assessment. It is noteworthy that distribution of response frequencies among the response options available was homogeneous. For example, most responses were those scored 1 or 2, with a maximum response frequency of 0.50 (item No. 48). Responders selected the responses scored 3 more frequently than those scored 0. This distribution of response frequencies among the response options indicates high internal consistency and criterion validity of the WOCQ, and that responders understood the questions correctly.

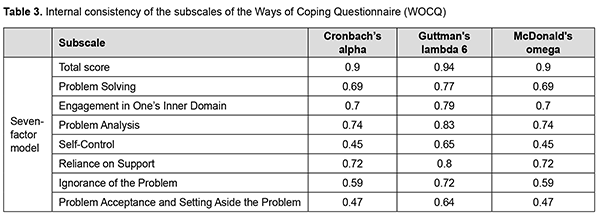

Item sets, or subscales, of a seven-factor model of the WOCQ for emergency situations were assessed for internal consistency reliability by computing Cronbach’s alpha, Guttman's lambda 6, and McDonald's omega (Table 3).

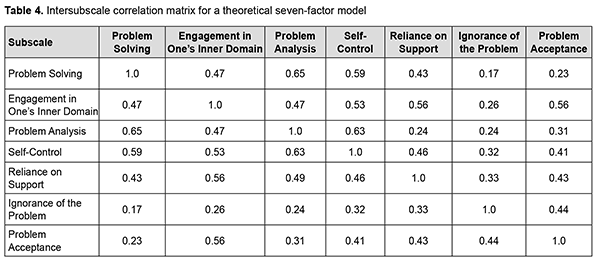

In general, most subscales demonstrated high internal consistency reliability (nonstandardized Cronbach’s alpha), but some subscales (e.g., Self-Control and Problem Acceptance and Setting Aside the Problem) demonstrated low internal consistency reliability. Subsequently, a modified alternative five-factor model of the questionnaire was proposed on the basis of the results of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis (see below). The correlation analysis was used to investigate the relationships among subscales of the questionnaire, with an intersubscale correlation matrix being created (Table 4).

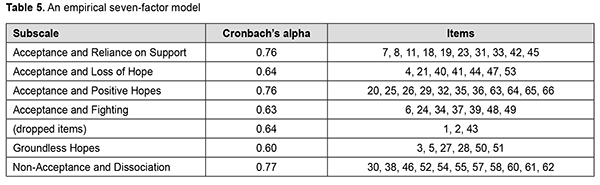

The correlation matrix showed no multicollinearity, and inspection of the matrix showed that all correlation coefficients were positive. All interscale correlations were moderate indicating that, although related, they are assessing distinct components of the construct. The factor analysis of the seven-factor model of the WOCQ was performed using exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. At the first stage of the analysis, the exploratory method was employed to assess an original seven-factor model, showing how each item loaded of each factor. The maximum likelihood method with oblique rotation (direct oblimin) was used to alter the pattern of factor loadings; this resulted in creating an empirical seven-factor model, which was subsequently modified and reduced to a five-factor model. Table 5 presents the results of the reliability analysis and the new pattern of factor loadings for the empirical seven-factor model, with specification of Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficients and the new subscales. Interfactorial correlations ranged from 0 to 0.30, with the exception of the correlation between the first and the seventh factors and between the sixth and the seventh factors, which were 0.34.

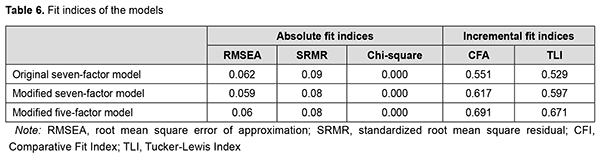

We tried to obtain further model modifications. Thus, nine factors were obtained using the Cattell scree plot. A theoretical model was tested, and, on its basis, an empirical seven-factor model was created, which was modified and reduced to a five-factor model. Table 6 shows fit indices for all the models created.

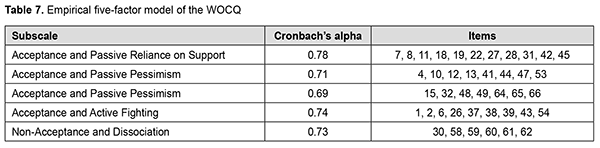

Twenty four items (Nos. 3, 5, 9, 14, 16, 17, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25, 29, 34, 35, 36, 40, 46, 50, 51, 52, 55, 56, 57, and 63) were extracted to obtain a modified five-factor model, which enabled a more than one-point increase in incremental fit indices, thus improving model performance. In addition, we managed to substantially improve Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficients of the scales in the modified five-factor model. It is noteworthy that exploratory factor analysis and analysis of residual correlations found that high Cronbach’s alpha values were achieved somewhat at the expense of item redundancy. Table 7 shows Cronbach’s alpha values and lists of items that were left for the subscales of the five-factor model of the WOCQ.

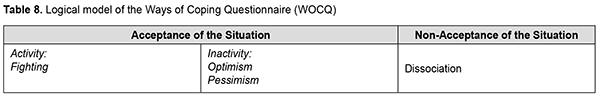

The subscales of the empirical five-factor model were examined, and proposed to be interpreted in a way described below. They are to be generally divided into those related to the acceptance, and those related to the non-acceptance of the situation (Table 1). The former subscales may be subdivided into “active” and “passive”. Both “active” subscales and “passive” subscales may be further subdivided into “optimistic” and “pessimistic” subscales. Non-Acceptance and Dissociation is a special subscale that is related to denial of reality (as a response to danger), but not to the active or passive position. In addition, the scales correspond to the physiological fight, flight, and freeze responses to danger.

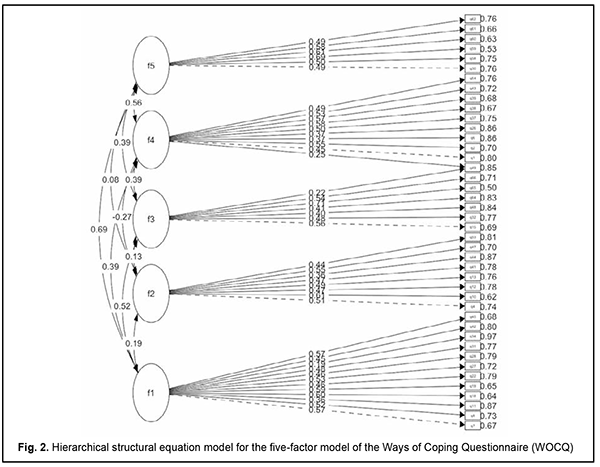

Interpreting The Acceptance and Passive Reliance on Support scale characterizes the person’s (1) tendency to perceive the events around him/her and stressful situations he/she encounters correctly, and (2) disability to act independently without assistance from others. This is some sort of a coping strategy of learned helplessness. The Acceptance and Passive Pessimism scale characterizes a passive coping strategy of being engaged in negative thoughts; the person understands and accepts the situation and assesses it correctly, but his/her activity remains cognitively blocked (just negative thoughts and no real actions). The Acceptance and Passive Optimism scale characterizes a passive coping strategy of freezing in stressful situations, disability to act and engagement in cognitive activity. “Toxic positivism” is a potential critical manifestation of passive optimism, some sort of coping behavior in response to danger or life-threatening situations, which is characterized by pathological optimism that affects the perception of real danger. The Acceptance and Active Fighting scale characterizes a fair and balanced analysis of the situation, with the person’s activity not being blocked. The Non-Acceptance and Dissociation scale characterizes denial of the real situation, engagement in one’s inner domain, and perception of events via a defense mechanism, as if they take place not in reality. Scale Scoring and Test Norms Items are presented on a Likert-type scale, and subscale scores are calculated by summing the items corresponding to that subscale. A total score may be calculated as well. Maximum subscale score equals 3 multiplied by the number of items in the scale. The example of calculation is made in percentages. Acceptance and Passive Reliance on Support: 11 * 3 = 33 (100%). An Acceptance and Passive Reliance on Support scale score of 11 to 22 is classified as that in the normal range and gives evidence of a generally rather marked feature, analysis of the situation, with the person’s activity not being blocked. Acceptance and Passive Pessimism: 8 * 3 = 24 (100%). An Acceptance and Passive Reliance on Support score of 8 to 16 is classified as that in the normal range. Acceptance and Passive Optimism: 7 * 3 = 21 (100%). An Acceptance and Optimism score of 7 to 14 is classified as that in the normal range. Acceptance and Active Fighting: 9 * 3 = 27 (100%). An Acceptance and Active Fighting score of 9 to 18 is classified as that in the normal range. Non-Acceptance and Dissociation: 7 * 3 = 21 (100%). A Non-Acceptance and Dissociation score of 7 to 14 is classified as that in the normal range. A hierarchical structural equation model was designed for the five-factor model (Fig. 2).

A concurrent validity of the WOCQ was assessed by comparing the results of the questionnaire with those of the Szondi Picture Selection Test [11] and an eight-factor model of the WOCQ for self-actualization situations as modified by Rodina [10]. There was low but sufficient correlation of 0.2 between the Acceptance and Passive Optimism scale and Epileptic Drive +. In addition, there was correlation of -0.12 between the Acceptance and Active Fighting scale and Katatonic Drive -. Moreover, there was correlation of -0.11 between the Non-Acceptance and Dissociation scale and Epileptic Drive +. There were sufficient correlations between the scales of the of the five-factor model of the WOCQ and the scales of the eight-factor model for self-actualization situations. Correlation of 0.88 between the Acceptance and Passive Reliance on Support scale and Seeking Social Support scale was the highest, followed by correlation of 0.76 between the Acceptance and Passive Optimism scale and Positive Reappraisal scale, and correlation of 0.67 between the Non-Acceptance and Dissociation scale and Wishful Thinking scale. Discussion Coping for adapting to difficult life situations has become an important subject of studies. Studies by Nosenko and colleagues [12], Chekhlatyi [13], Antonovsky [14]; Holahan and Moos [15], Losoya and colleagues [16], and Rodríguez and Garcelán [17] noted that, insufficiently developed adaptive and constructive coping strategies account for increased pathogenicity of life events, which may trigger psychosomatic and other disorders. Bodrov [18] believes that the idea of coping behavior implies various forms of human activity that embrace interactions of the personality with inner and outer problems. Coping behavior becomes activated when it is required to change one’s behavior in difficult life situations, in the chronic impact of stressors and negative everyday life events for adjusting the personality to the situation. Coping is aimed at looking at ways (1) to change the interrelationship between the subject and his/her environment or (2) to reduce his/her emotional discomfort and distress. Coping behavior of the personality is manifested cognitively, emotionally and behaviorally in the form of various strategies aimed at countering stress-inducing factors and situations. Psychometric instruments for studying coping are based on measurements of coping behavior and the potential for self-regulation in response to stress-inducing factors like threats to one’s life or health, disability, adaptation to life with disability, etc. It is noteworthy that our new psychodiagnostic tool may be especially useful in the war and early post-war period, because it is in the period of maximum stress load on the person (i.e., in a period of threats to life or health) that it has been developed. Studies of the adaptive capacity of these patients [5, 19] demonstrated that patients with eye disease develop special adaptive coping strategies to manage their condition. Therefore, we believe it is important to use psychodiagnostic tools in practice to assess (1) the adaptive capacity of eye care workers and patients with various eye diseases and (2) the opportunities for improving these capacities. Conceptualization of the construct of coping behavior consists primarily in (1) defining the construct as a process of constantly changing cognitive and behavioral efforts to meet internal and external needs and (2) expanding the individual’s psychic resource of coping (including with situations of danger). Some researchers like Billings and Moos [20] and Pearlin and Schooler [21] believe that active coping may attenuate the impact of acute life events and chronic stress factors. Therefore, it is believed that it is the assessment of coping behavior strategies that enables improved validity and reliability. A disadvantage of these studies is that the questionnaires are focused only on fundamental subjective assessments, but not on applied experimental research. In addition, when developing these psychodiagnostic tools, it is important to pay special attention on dividing groups into age subgroups, because the assessment of the situation of danger may depend on the age of the responder. Therefore, the Scale for Assessing Coping Behavior in Situations of Danger developed may become a reliable psychodiagnostic tool for assessing adults and for comparing batteries of tests of individual’s behavior in situations of danger, stress and emergency, to improve the adaptive capacity of the individuals that have suffered from the situation of Russian invasion. For example, a high Non-Acceptance and Dissociation score indicates that the respondent should have a more detailed differential diagnostic evaluation for other mental health disorders. High Acceptance and Passive Pessimism and Acceptance and Passive Reliance on Support scores may indicate that a respondent has a tendency to “positive dissociation” (escape from reality into a happy world of illusion). Conclusion In conclusion, a Ukrainian-language Scale for Assessing Coping Behavior in Situations of Danger was developed on the basis of the Folkman & Lazarus Ways Of Coping Questionnaire (WОСQ) as modified by Rodina. The modified five-factor version includes the following subscales: Acceptance and Passive Reliance on Support, Acceptance and Passive Pessimism, Acceptance and Passive Optimism, Acceptance and Active Fighting, and Non-Acceptance and Dissociation. That is, coping behaviors in situations of danger may be generally divided into acceptance and non-acceptance (dissociation), and the former may be subdivided into passive and active acceptance. The analysis was conducted in the following sequence: exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis was used to review and assess an original seven-factor model, and an empirical seven-factor model was created, which was subsequently modified and reduced to a five-factor model, with some of the items being dropped, and the remaining items being resorted. This enabled to make a questionnaire model shorter and improve scale reliability, fit indices and construct and criterion validity. It was demonstrated that application of the method for assessing coping behavior in situations of danger is promising and of increasing importance for further studies in order to improve the adaptive capacity in situations of life threat, war, danger, etc. The five-factor model of the Scale for Assessing Coping Behavior in Situations of Danger created involves 42 items and meets commonly accepted minimum standards of reliability for questionnaires.

References: 1.Tsekhmister IV, Daniliuk IV, Rodina NV, Biron BV, Semeniuk NS. [Developing a stress reaction inventory for eye care workers]. J Ophthalmol (Ukraine). 2019;1(486):39-45. Ukrainian. 2.Rodina NV, Biron BV, Ukhanova AI, Semenyuk NS, Kernas AV. [Developing the interrole conflict scale for eye-care workers. J Ophthalmol (Ukraine). 2020;2(493):79-86]. Ukrainian. 3.Vlasova OI , Rodina NV, Tselikova YuO, Vornikova LK, Tykhonenko YuO. [Modifying, standardizing and adapting the Adverse Childhood Experience Questionnaire]. J Ophthalmol (Ukraine). 2010;5 (490): 30-36. Ukrainian. 4.McKinley N, McCain RS, Convie L, et al. Resilience, burnout and coping mechanisms in UK doctors: a cross sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020 Jan 27;10(1):e031765. 5.Anil K, Garip G. Coping strategies, vision-related quality of life, and emotional health in managing retinitis pigmentosa: a survey study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2018 Jan 30;18(1):21. 6.Folkman S, Lazarus RS. An analysis of coping in a middle-aged community sample. J Health Soc Behav. 1980 Sep;21(3):219-39. 7.Folkman S, Lazarus R.S. Manual for the Ways of Coping questionnaire [Research Edition]. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists.1988:32. 8.Rodina NV. [Psychometric analysis and standardization of the WOCQ questionnaire for assessing coping behavior under extreme stress]. Bulletin of the Odessa National University. 2010;15 (11):137–47. Ukrainian. 9.Khairova SI. [On developing an adapted version of the WOCQ technique]. Praktychna Psychologiia i Sotsialna Robota] . 2003;1:9–16. Russian. 10.Rodina NV. [Meaningful and convergent validity of the WOCQ questionnaire for situation of threat to self-actualization and life]. Bulletin of the Kherson State University. Psychological Sciences Series. 2014;1(1):78-84. Ukrainian. 11.Szondi L. Szondi L. Lehrbuch der Experimentellen Triebdiagnostik. Bern: Hans-Huber Verlag, 1972. 12.Nosenko EL, Arshava IF, Kutovyi KP. [Forms of reflected assessment of emotional stability and emotional intelligence of man: a monograph]. Dnipro: Inovatsiia; 2011. Ukrainian. 13.Chekhlatyi EI. [Personal and interpersonal conflict and coping behavior in patients with neuroses and their longitudinal changes with group psychotherapy]. Abstract of Thesis for the Degree of Cand Sc (Med). Saint Petersburg; 1994. Russian. 14.Antonovsky A. Personality and health: Testing the sense of coherence model. In: Friedman HS, editor. Personality and Disease. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 155–77. 15.Holahan CJ, Moos RN. Life stressors, resistance factors, and improved psychological functioning: an extension of the stress resistance paradigm. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990 May;58(5):909-17. 16.Losoya S, Eisenberg N, Fabes RA. Developmental issues in the study of coping. Int J Behav Dev. 1998;22(2):287–313.Crossref 17.Rodríguez AG, Garcelán SP. Algunas aportaciones críticas en torno a la búsqueda de un marco teórico del afrontamiento en la psicosis de un marco teorico del afrontamiento en la psicosis. Psicotema. 2001;4:563-70. 18.Bodrov VA. [The problem of coping with stress. «COPING STRESS» and theoretical approaches to its study]. Psikhologicheskii zhurnal. 2006;27(1):122-33. Russian. 19.Glen FC, Crabb DP. Living with glaucoma: a qualitative study of functional implications and patients’ coping behaviours. BMC Ophthalmol. 2015;15(1):57-69. 20.Billings AG, Moos RH. The role of coping responses and social resources in attenuating the stress of life events. J Behav Med. 1981 Jun;4(2):139-57. 21.Pearlin LI, Schooler С. The structure of coping. J Health Soc Behav. 1978 Mar;19(1):2-21.

Disclosures Conflict of interest: The authors state that there is no conflict of interest that could affect their opinion on the subject or materials of this manuscript. Sources of support: none.

|