J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2019;1:39-45.

|

http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh201913945 Received: 22 November 2018; Published on-line: 28 February 2018 Developing a stress reaction inventory for eye care workers Tsekhmister I.V.,1 Dr Sc (Pedagogics), Prof., Corresponding Member of NAPS of Ukraine; I.V. Daniliuk,2 Dr Sc (Psychology), Prof.; N.V. Rodina3, Dr Sc (Psychology), Prof.; B.V. Biron3, Cand Sc (Psychology); N.S. Semeniuk, 4 Cand Sc (Psychology) 1 Bogomolets National Medical University; Kyiv (Ukraine) 2 Taras Shevchenko Kyiv National University; Kyiv (Ukraine) 3 Mechnikov Odesa National University; Odessa (Ukraine) 4 IQVIA RDS Ukraine; Odessa (Ukraine) TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Tsekhmister IV, Daniliuk IV, Rodina NV, Biron BV, Semeniuk NS. Developing a stress reaction inventory for eye care workers. J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2019;1:39-45.http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh201913945 Background: The job-related burnout rate in eye care workers has been consistently rising. That is why it is important to develop psychodiagnostic instruments for detecting stress reactions, and to make them psychometrically adapted to the social and cultural realities of the Ukrainian professional environment. Purpose: To develop an inventory for measuring stress reactions, to customize it to eye care workers and the realities of our nation, to psychometrically analyze it, and to estimate its relationships with job satisfaction indices. Materials and Methods: The study sample consisted of the eye care workers from the Filatov institute. Two hundred and eleven eye care workers were included in the study. The response rate for the inventory was 85.8% (181/211). The 181 responders included 99 nursing staff members and 82 physicians (ophthalmologists). The study was conducted with the use of the modified version of the Student-life Stress Inventory (SSI) by Gadzella. Results: The Stress Reaction Inventory (SRI) for eye care workers was developed by adapting the SSI. The modified version of the inventory is comprised of four stress reaction scales (or categories), Physiological (F), Emotional (G), Behavioral (H), and Cognitive Appraisal (I), which were found to have high internal consistency and test-retest reliability. Both among the nursing staff member group and the physician group, the more acute emotional and behavioral reactions to stressors responders experienced, the lower was their job satisfaction. The test norms were developed and presented using the quartile scale, as long as the sample was representative. Therefore, the adapted Ukrainian-language version of the Stress Reaction Inventory for eye care workers showed evidence of internal consistency and construct validity. Keywords: stress reactions, job satisfaction, inventory, standardization, ophthalmologists

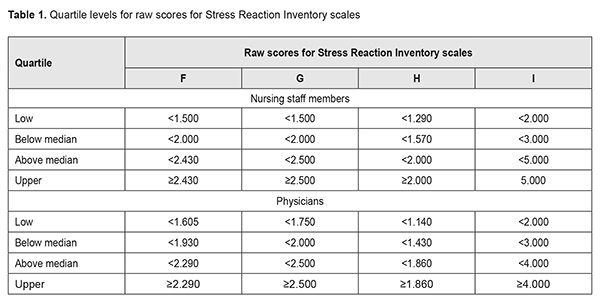

Introduction While considering stress issues related to professional medical activities, it should be noted that these activities are characterized by high frequency of negative stress events, marked individual stress loads, and increased maladaptive stress responses. Recent reviews [1, 2] of empirical studies have evidenced that doctors of various specialties are rather sensitive to workplace stress. Little is, however, known on which stress responses are characteristic of eye care workers [3]. Therefore, the purpose of this article was to develop an inventory for measuring stress reactions, to customize it to eye care workers and the realities of our nation, to psychometrically analyze it, and to estimate its relationships with job satisfaction indices. Material and Methods The study sample consisted of the eye care workers from the Filatov institute. Two hundred and eleven eye care workers were requested to respond to the inventory. The response rate for the inventory was 85.8% (181/211). The 181 responders included 99 nursing staff members, and 82 ophthalmologists. The SRI for eye care workers was developed by adapting the Student-life Stress Inventory (SSI) by Gadzella [4]. The SSI of 1991 consists of 51 items and is comprised of two subscales representing nine categories. The subscales are identified as Stressors and Reactions to Stressors with five categories specific to Stressors and four associated with Reactions to Stressors. The five categories of Stressors include Frustrations (A), Conflicts (B), Pressures (C), Changes (D), and Self-Imposed (E). The four categories representing Reactions to Stressors are Physiological (F), Emotional (G), Behavioral (H), and Cognitive Appraisal (I). The responders rate each item by using a 5-point Likert scale. Items of the Cognitive Appraisal category have reversed scaling. Gadzella et al found SSI categories such as Frustrations (A), Conflicts (B), Pressures (C), Changes (D), Self-Imposed (E), Physiological (F), Emotional (G), Behavioral (H), and Cognitive Appraisal (I) to have a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.67, 0.71, 075, 0.86, 0.61, 0.83, 0.82, 0.73, and 0.77, respectively. In 2015, the SSI was translated into Ukrainian, and customized to the social and cultural realities of our nation by Biron [5]. The customization was based on the principles of Daniliuk’s ethnonational psychology. According to Daniliuk [6], ethnic identity is a factor in personality self-building. In the customized version of 2015, the B and E categories of the original version were removed for the following two reasons. First, responders found it difficult to understand formulations of the B category items related to quantitative and qualitative characteristics of alternatives for conflict situations. Second, E category items were too subjective and related to self-assessment of personality characteristics. The responders rate each item by using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = Never, 2 = Seldom, 3 = Occasionally, 4 = Often, and 5 = Most of the Time. The Kim, Leong, and Lee’s Job Satisfaction Scale (JSS) [7] was translated into Ukrainian and psychometrically analyzed by Semeniuk [8] based on the conditions of the national eye care worker population, and used for the assessment of job and organization satisfaction. The scale consists of 5 items describing a subjective assessment of individual’s job. The responders rate each item by using a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, and 5 = Strongly Agree. The JSS was found to have a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.849 [9]. Psychometric indices characterizing internal scale consistency were calculated for each scale or category. Values for each item were standardized before computing Cronbach’s alpha. According to Burlachuk [10], inventory scales most commonly have a Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.6 to 0.8. In the current study, a Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.6 to 0.8 was considered as satisfactory, and that exceeding 0.8 was considered as high. EZR (R-statistics) software [11] was used for statistical analyses. Results The Stress Reaction Inventory (SRI) for eye care workers was adapted from the instrument by Gadzella et al [4]. The SRI is comprised of the following scales (categories representing Reactions to Stressors): Physiological (F), Emotional (G), Behavioral (H), and Cognitive Appraisal (I). The Physiological (F) scale describes the symptoms (sweating; speech difficulties; trembling; restlessness; exhaustion, etc.) that the responder may have experienced recently. The scale comprises 14 items. It demonstrated high internal consistency for a general sample of medical staff (as reflected by a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.835) and subsample of nursing staff (0.868), and sufficient internal consistency for a subsample of physician staff (0.746). The Emotional (G) scale describes the symptoms (fear, anxiety, worry, anger, guilt, etc.) that the responder may have experienced recently. The scale comprises 4 items. It demonstrated sufficient internal consistency for a general sample of medical staff, subsample of nursing staff, and subsample of physician staff, as reflected by a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.738, 0.728, and 0.756, respectively. The Behavioral (H) scale describes the reactions that the responder may have experienced in stressful situations such as crying, abusing others, alcohol or drug abusing, etc. The scale comprises 7 items. It demonstrated sufficient, high and low internal consistency for a general sample of medical staff, subsample of nursing staff, and subsample of physician staff, respectively, as reflected by a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.776, 0. 820, and 0.587, respectively. We found that the item ‘I have cried in a stressful situation’ (item 19) contributed the least to the internal consistency of the Behavioral (H) scale for a subsample of physician staff (Cronbach’s alpha if item is deleted = 0.612). We decided to remove this item from the scale, since the scale as well as the entire SSI was originally developed for use with students, not medics. However, as a person grows older, the number of his /her crying events decreases and emotions become a more common reason for crying than physical pain [12]. Therefore, after removing the item, the reliability, as expressed by Cronbach's alpha, improved to 0.817 (high level), 0.865 (high level), and 0.624 (sufficient level) for the Behavioral (H) scale for a general sample of medical staff, subsample of nursing staff, and subsample of physician staff, respectively. The Cognitive Appraisal (I) scale describes the ideas and analysis with regard to stressful situations, stress level assessment, and stress coping efficacy assessment. The scale comprises 2 items. It demonstrated high internal consistency for a general sample of medical staff (as reflected by a Cronbach's alpha value of 0.921), subsample of nursing staff (0.868), and subsample of physician staff (0.941). Pearson correlations demonstrated high test-retest reliability across two test sessions separated by two weeks. Thus, Pearson coefficients for the Physiological (F), Emotional (G), Behavioral (H), and Cognitive Appraisal (I) scales were 0.786, 0.799, 0.834, and 0.765, respectively, among the nursing staff, and 0.823, 0.809, 0.896, and 0.798, respectively, among the physician staff. The last stage of the psychometric analysis for this methodology consisted in examination of the descriptive statistics for constructed scales. Descriptive statistics for the Physiological (F), Emotional (G), Behavioral (H), and Cognitive Appraisal (I) scales were (M = 1.927; SD = 0.491), (M = 2.107; SD = 0.698), (M = 1.556; SD = 0.426), and (M = 2.951; SD = 1.246), respectively, among the nursing staff subsample, and (M = 2.069; SD = 0.724), (M = 2.139; SD = 0.811), (M = 1.782; SD = 0.765), and (M = 3.157; SD = 1.437), respectively, among the physician staff subsample. A comparison among contrast groups with regard to intensity of reactions to the stressors was performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. However, the test found no significant differences with regard to the Physiological (U = 3824.500; p = 0.503), Emotional (U = 4039.500; p = 0.955), Behavioral (U = 3477.500; p = 0.095), and Cognitive Appraisal (U = 3701.500; p = 0.304) reactions to the stressors. Criterion-related validity was assessed by Spearman’s correlation between Stress Reaction Inventory scales and the Job Satisfaction Scale. Spearman correlation coefficients for the Physiological, Emotional, Behavioral, and Cognitive Appraisal scales were (rs = -0.179; p = 0.077), (rs = -0.316; p = 0.001), (rs = -0.230; p = 0.022), and (rs = 0.230; p = 0.022), respectively, among the nursing staff subsample, and (rs = -0.301; p = 0.006), (rs = -0.348; p = 0.001), (rs = -0.241; p = 0.029), and (rs = 0.018; p = 0.869), respectively, among the physician staff subsample. The last stage of the study was to standardize the Stress Reaction Inventory. We believe that the sample studied in this research can be used to standardize the inventory, and that the norms calculated for the sample are representative for the individuals of relevant age and social status. This makes it possible to introduce relevant test norms. The method selected for reducing normalized estimates to the easy-to-use form boils down to presenting final test estimates using a quartile scale (Quartile 1, lower quartile; Quartile 2, below median; Quartile 3, above median; Quartile 4, upper quartile). Table 1 shows (1) raw index scores corresponding to defined standardized index levels in accordance with calculated quartile estimates and (2) test norms expressed in quartiles.

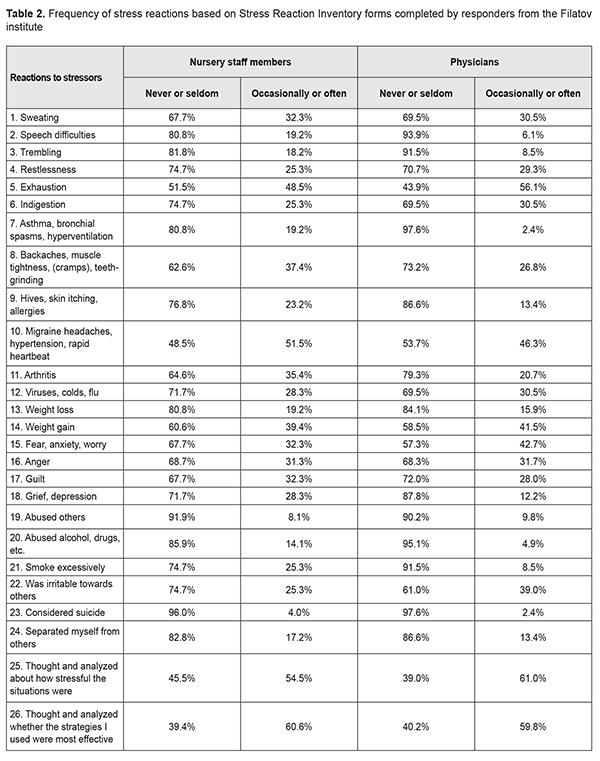

In order to compare the data we obtained on the frequency of stress reactions experienced by Ukrainian eye care workers with those reported by other researchers, we conducted frequency analysis of stress reactions as per the Stress Reaction Inventory suggested by us. Table 2 demonstrates frequencies of reactions to physiological, emotional, and behavioral stressors, and cognitive appraisal of stressors based on Stress Reaction Inventory forms completed by responders from the Filatov institute.

Discussion Ophthalmology is a high-tech and fast advancing branch of medicine, and its recent advances have raised the bar of expectations for successful treatment of eye disorders for patients. However, significant workload [13] and demand for constant learning in order to comply with best practices and standards in medical care may become stressors for physicians [14]. A job-related burnout rate in eye care workers has been consistently rising. Job-related burnout is defined in clinical psychology as an emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and reduced personal accomplishment that can occur among individuals who work with other people in some capacity [15]. In addition, ICD-10 defines burnout as a “state of vital exhaustion” [16]. Recent studies have demonstrated that burnout is associated with reduced job performance and a risk factor for coronary heart disease [17]. Chronic burnout is also associated with impaired cognitive performance (impaired memory and attention performance), absence at work and job withdrawal intentions [18]. We believe that stress coping bust be viewed as a system phenomenon [19, 20]; however, it is noteworthy that the psychodiagnostic instruments for the assessment of stress reactions in eye care workers are unavailable, and the use of non-validated [21-23] or non-specialized psychometric questionnaires [24] is common among studies. That is why a Stress Reaction Inventory (SRI) for eye care workers customized to the Ukrainian setting was developed and psychometrically analyzed, and its relationships with job satisfaction indices were estimated. We have compared the frequencies of stress reactions obtained with the SRI in our study sample with those obtained in other studies. It has been reported [25] recently that, of the US ophthalmologists surveyed, 37% said that they are either burned out, depressed, or both, and 23%, that they would seek professional help for burnout, depression or both. In addition, close to half (46%) of ophthalmologists who acknowledged having depression reported that they express their frustration around staff and peers as a result. Moreover, 38% percent said that they are more easily exasperated, and 33% are either less engaged or less friendly with friends and colleagues. In a Pakistani study by Alkhairy et al [21], phaco surgeons were requested to fill in a questionnaire which described the physical symptoms of stress such as headache, dry mouth, palpitations etc which one experiences while doing phacoemulsification surgery and also inquired about the surgical experience. Stress level was found to be the highest in 6–14 years working experience. In an Iranian study by Chams et al [26], ergonomics-related disorders (like back pain) and such stress-related disorders as chronic headache and psychosocial disorders were reported by 80%, 54.9%, and two thirds, respectively, of the responding ophthalmologists. In the current study, we found that, among Ukrainian ophthalmologists, cognitive reactions were more common than physiological, emotional, and behavioral reactions to stressors. Cognitive reactions to stressors are associated with threat appraisal, decision making with regard to stressful situations, and planning for further actions, which is the most important in the interaction of the human being with the environment, and facilitates effective stress coping. We found exhaustion to be the most common physiological reaction both among nursing staff members and physicians (48.5% and 56.1%, respectively). In addition, the most common emotional reactions among physicians were fear, anxiety, and worry (42.7), but various emotional reactions were approximately equally common among the nursing staff members. Furthermore, the most common behavioral reaction among physicians was irritation (39.0%). That is, the above reactions to stressors are characteristic for ophthalmologists from various countries and were found with various frequencies among studies. This is in agreement with previous empirical studies which demonstrated that the within-person variability in job performance was associated with a variety of specific stress reactions like worry, irritation, depressive symptoms, hostile attitude and loneliness. Therefore, the final Cronbach’s alpha coefficients and test-retest correlation coefficients obtained in the current study make it possible to conclude that the scales of the modified Stress Reaction Inventory (SRI) version had high internal consistency and test-retest reliability, and can be used for further psychometric research among eye care workers. It was found that intensity of stress reactions did not depend on whether an eye care worker was a nursing staff member or a physician. In addition, burnout was found with the same frequency in nursing staff members as in physicians. Both among the former and the latter groups, the more acute emotional and behavioral reactions to stressors responders experienced, the lower was their job and organization satisfaction. Moreover, the more acute physiological reactions physicians experienced, the lower was their job satisfaction. Furthermore, among nursing staff members, the capacity for cognitive appraisal of stressful events and appraisal of stressfulness and efficacy of coping strategies contributed to their higher job and organization satisfaction. The most common stress reactions among Ukrainian eye care workers were cognitive stress reactions, namely, cognitive appraisal of and coping with stressful events. The use of the Stress Reaction Inventory (SRI) developed by us would enable correlating the data of further studies with the results of the current study. Incorporation of the standardized inventory into test batteries would facilitate forming comprehensive diagnostic test batteries, which may be widely used for assessing effectiveness of psychological support for eye care workers. The inventory (or questionnaire) is provided in the Appendix. References

1.Bragard I, Dupuis G, Fleet R. Quality of work life, burnout, and stress in emergency department physicians: a qualitative review. Eur J Emerg Med. 2015 Aug;22(4):227-34. 2.Regehr C, Pitts A, Leblanc VR. Interventions to reduce the consequences of stress in physicians: a review and meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202:353–9. 3.Ulrich LR, Lemke D, Erler A, Dahlahaus A. [Subjective and objective work stress among ophthalmologists in private practice in Thuringia: Results of a state-wide survey]. Ophthalmologe. 2018 Oct 22. German. 4.Gadzella BM, Fullwood HL, Ginther DW. Student-life Stress Inventor. Texas Psychological Convention. San Antonio ERIC; 1991. p. 345-50. 5.Biron BV. [Proactive coping with stressful situations]. [Abstract of Cand Sc (Psychology) Thesis]. Odesa: Mechnikov National University; 2015. 22 p. Ukrainian. Available at: http://dspace.onu.edu.ua:8080/handle/123456789/10687 6.Daniliuk IV. [Ethnic identity as a factor in personality self-building. Psychological and pedagogical basics of personality self-building]. Kyiv: Pedagogichna dumka; 2015. p. 68-81. Ukrainian. 7.Kim WG, Leong JK, Lee YK. Effect of service orientation on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intention of leaving in a casual dining chain restaurant. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2005; 24:171-93. 8.Semeniuk NS. [Psychological features of individual’s life orientations]. [Cand Sc (Psychology) Thesis]. Odesa: Mechnikov National University; 2018. Ukrainian. 9.Anafarta N. The Relationship between Work-Family Conflict and Job Satisfaction: A Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) Approach. International Journal of Business & Management. 2011;6(4):168-177. 10.Burlachuk LF. [Psychodiagnostics: A textbook for universities]. Saint Petersburg: Piter Publishing house; 2006. Russian. 11.Gur’ianov VG, Liakh II, Parii VD, Korotkyi OV, Chalyi OV, Tsekhmister IV. [Analysis of the results of medical studies using EZR (R–statistics) software: Biostatistics training manual]. Kyiv: Vistka; 2018. Ukrainian. 12.Martynova EM. [Cry and its definition within the framework of anomalous communication.]. Filologicheskiie nauki. Voprosy teorii i praktiki. 2014;1(31 Pt1):86-9. Russian. 13.Saksonov SG, Gruzeva TS, Vitovska OP. Health of ophthalmologists as a prerequisite of quality medical services. Wiad Lek. 2018; 71(1):165-7. 14.Nair AG, Jain P, Agarwal A, Jain V. Work satisfaction, burnout and gender-based inequalities among ophthalmologists in India: A survey. Work. 2017;56(2):221-228. 15.Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach Burnout Inventory: third edition In: Zalaquett CP, Wood RJ., editors. Evaluating stress: a book of resources. Lanham (MD): Scarecrow Press; 1998. p. 191–218. 16.ICD-10. Available at: http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2016/en#/Z73.0 17.Toker S, Melamed S, Berliner S, Zeltser D, Shapira I. Burnout and risk of coronary heart disease: a prospective study of 8838 employees. Psychosom Med. 2012 Oct;74(8):840-7. 18.Sandstrom A, Rhodin IN, Lundberg M, Olsson T, Nyberg L. Impaired cognitive performance in patients with chronic burnout syndrome. Biol Psychol. 2005 Jul;69(3):271-9. 19.Rodina NV. [Psychology of Coping Behavior: System Simulation]. [Abstract of Dr Sc (Psychology) Dissertation]. Odesa: Mechnikov National University; 2004. 22 p. Ukrainian. Available at: http://dspace.onu.edu.ua:8080/handle/123456789/4098 20.Rodina NV. The area of the psychological phenomena system modeling in Ukraine: development, results and prospects of research. Fundamental and Applied Researches In Practice of Leading Scientific Schools. 2017. 21(3):56-60. https://farplss.org/index.php/journal/article/view/179 21.Alkhairy S, Siddiqui F, Mirza AA, Adnan S. Stress and Phacosurgeon: An Unavoidable Association. Pak J Ophthalmol. 2016; 32(4):221-5. 22.Stewart WC, Stewart JA, Adams MP, Nelson LA. Survey of practice-related stress among United States and European ophthalmologists. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011 Sep;249(9):1277-80. 23.Viviers S, Lachance L, Maranda MF, Menard C. Burnout, psychological distress, and overwork: The case of Quebec's ophthalmologists. Can J Ophthalmol. 2008 Oct;43(5):535-46. 24.Honavar SG. Brace up or burnout. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018 Apr;66(4):489-90. 25.Medscape Ophthalmologist Lifestyle Report 2018: Personal Happiness vs. Work Burnout. [Last accessed on 2018 Mar 20]. Available from: https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2018-lifestyle-ophthalmologist-6009233#1. 26.Chams H, Mohammadi SF, Moayyeri A. Frequency and assortment of self-report occupational complaints among Iranian ophthalmologists: a preliminary survey. MedGenMed. 2004 Dec 13;6(4):1.

|