J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2022;1:44-50.

|

http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh202214450 Received: 10 October 2021; Published on-line: 15 March 2022 Comparison of ophthalmological standards applicable to drivers in Poland and the United Kingdom with the European Union recommendations Wiktor Stopyra MW-med Eye Centre; Cracow (Poland) E-mail: wiktorstopyra@gmail.com TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Stopyra W. Comparison of ophthalmological standards applicable to drivers in Poland and the United Kingdom with the European Union recommendations. J.ophthalmol.(Ukraine).2022;1:44-50. http://doi.org/10.31288/oftalmolzh202214450 Each country has its own specific requirements with regard to the visual standards applicable to drivers. The following were summarised in the appropriate tables: 1) data contained in the Ordinance of the Minister of Health from the 30th of August 2019 regarding medical examinations of applicants for driving licences and drivers; 2) Directive 2006/126/EC of the European Parliament and the Council on driving licences updated on the 22nd of July 2018; 3) the government and nonprofit websites: Advice for Medical Professionals to Follow when Assessing Drivers with Visual Disorders updated on the 4th of March 2020. Both in Poland and the UK the required visual acuity of car and motorcycle drivers is 0.5, which is in line with the EU recommendations. The visual field of both eyes for car and motorcycle drivers with limit values horizontal ≥ 120°, range ≥ 50° right and left and ≥ 20° up and down is identical in Poland and the UK and coincides with the EU recommendations. Colour vision for drivers in the UK is not required, which is consistent with the EU recommendations, whereas in Poland, car and motorcycle drivers do not have to recognise colours, but bus and lorry drivers must correctly recognise red, green and yellow. Current minimum visual requirements for drivers in Poland are closely integrated with the EU recommendations and are similar to the criteria in the UK. They are not too strict but are sufficient to maintain safe driving and there is still a possibility of their liberalization. Кey words: automobile driving; visual acuity; binocular vision; visual fields; color vision; reference standards

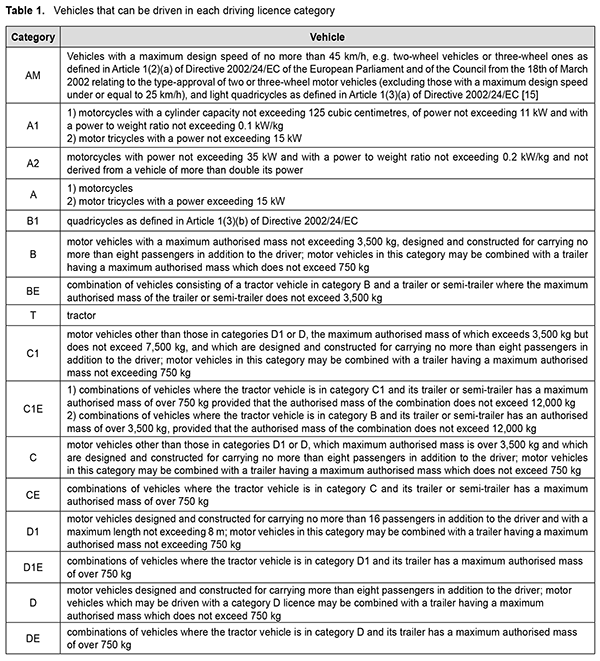

Introduction. Wilhelm II Hohenzollern, the last German Emperor and King of Prussia, was wrong in saying the famous words: ‘I think a car is a temporary phenomenon. I believe in a horse’. The car is currently a widely used commodity, not a short-lived trend. Driving is the primary means of transportation among the elderly in the United States of America [1] and is becoming increasingly important in Europe [2]. Although many medical factors contribute to safe driving, crash rates and driving-related injuries have been associated with deteriorating vision [3,4]. Therefore, one has to prove adequate health conditions to drive a car, especially when it comes to eyesight. The eternal dilemma has been acknowledging minimum requirements of the ophthalmic parameters that a driver must demonstrate to drive safely on the road. Each country has specific requirements for drivers in this respect [5 – 10]. It is gathered in the Ordinance of the Minister of Health from the 30th of August 2019 on medical examinations of applicants for driving licences and drivers (Law Journal of 2019, item 1659) in Poland [11]. In the UK, the information is available in the Advice for Medical Professionals to Follow when Assessing Drivers with Visual Disorders (last update from the 4th of March 2020) [12]. The EU similarly has its own recommendations published in Annexe III of Directive 2006/126/EC of the European Parliament and the Council from the 20th of December 2006 on driving licences (last update as of the 22nd of July 2018) [13]. So far, there are very few comparative studies in the world literature concerning the ophthalmic standards applicable to drivers in different countries. The studies that exist are sketchy, out of date and inaccurate [7, 10]. The purpose of the study was to review ophthalmological criteria required from drivers in Poland and the UK and comparing them with the EU recommendations. The most important functions of the eye, such as visual acuity, visual field, colour vision, binocular vision, glare sensitivity, mesopic vision and contrast sensitivity, were reviewed. The choice of countries is not random. Poland is constantly adjusting its standards to UE recommendations [11, 14], while the UK as an island country has always differed from the continent (left-hand car traffic, different measurement system etc). Although the European Union countries have their individual driving licence guidelines, the EU can potentially overrule these. That is the reason why the European Union ophthalmological standards had also been reported. Methods Sources included current legal acts, ordinances and directives, government and non-profit websites, as well as study reports and journal articles. The relevant legal acts in force in Poland and the UK were found on government websites (respectively www.sejm.gov.pl and www.gov.uk) while access to the European Union law was provided by the website www.uer-lex.europa.eu. This review includes papers concerning ophthalmological criteria applicable to drivers published in 2000-2020. The papers were identified by literature search of medical and other databases (MEDLINE, Web of Science, SciELO, SCIRUS, RSCI, Google Scholar, Cochrane Library) using the terms "drivers" and "vision" or "ophthalmological norms". After the preliminary hand-search only18 papers were selected for further analysis. Results In Poland, an ophthalmological driving test should include: • Visual acuity without and with compensation • Binocular best-corrected visual acuity • Visual field • Colour recognition • Binocular vision • Glare sensitivity • Mesopic vision • Contrast sensitivity [15] In accordance with the law in Poland, many vehicle categories were distinguished, which is similar to Directive 2002/24/EC of the European Parliament and the Council [16]. Details are collected in Table 1.

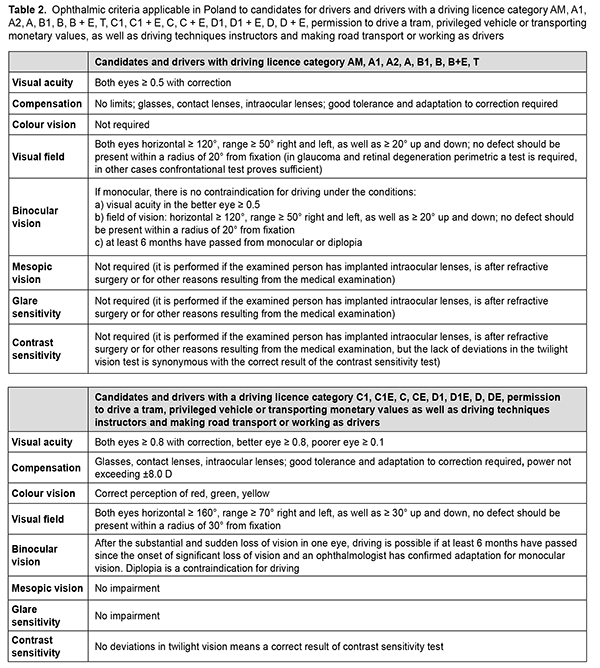

Annexe No 2 to the Ordinance of the Minister of Health from the 30th of August 2019 (Law Journal of 2019, item 1659) on medical examinations of applicants for driving licences and drivers precisely sets ophthalmological norms in this field. Detailed ophthalmological criteria for drivers and candidates for drivers for individual driving licence categories are presented in Table 2 [11].

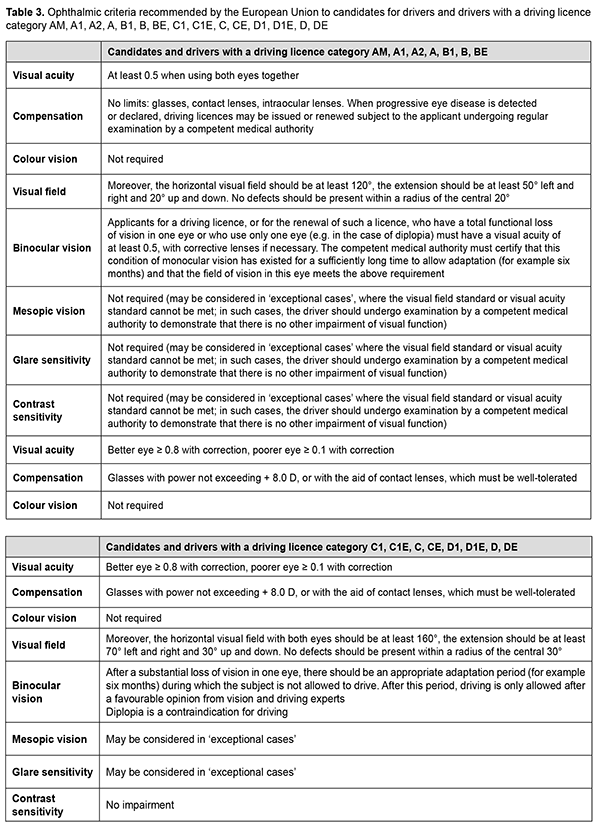

In the European Union, issues related to driving licences are precisely regulated by the Directive 2006/126/EC of the European Parliament and the Council from the 20th of December 2006 on driving licences (last update as of the 22nd of July 2018). Its Annexe III precisely sets the minimum requirements for the physical and mental ability for driving motor vehicles. Detailed ophthalmic parameters for candidates and drivers recommended by the European Union are presented in Table 3 [13].

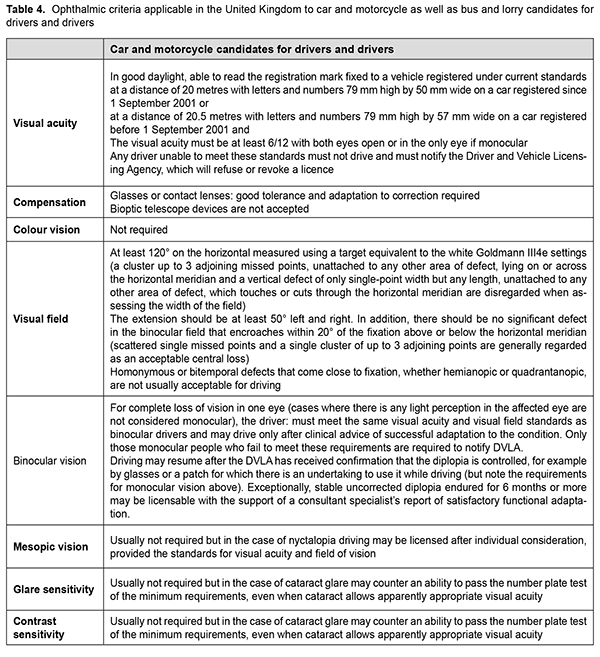

The Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency publishes health criteria relevant for assessing driving ability in the UK. The precise parameters of the organ of vision required from drivers are contained in the Advice for Medical Professionals to Follow when Assessing Drivers with Visual Disorders (last update as of the 4th of March 2020). The most important data from this document are shown in Table 4 [12].

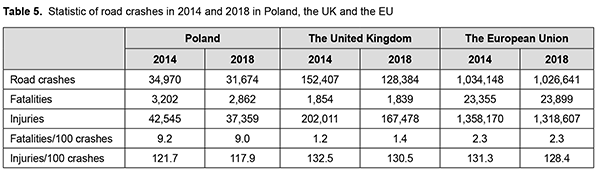

Discussion It is worth noting that both in Poland and the UK the required visual acuity of car and motorcycle drivers is 0.5, which is in line with the EU recommendations [11–13]. There is an additional condition of ability to read the registration mark fixed to a vehicle at a distance of 20 meters in the UK [6, 12, 17]. The visual field for car and motorcycle drivers with limit values of 120°, 50° and 20° is identical in Poland and the UK and coincides with the EU recommendations [11-13]. Similar ophthalmological criteria for obtaining a driving licence are binding for monoculars both in Poland and the UK and match the EU recommendations (VA = 0.5 and adaptation to monocularity required; 6 months from the start of monocularity) [11–13]. Poland only complied with these guidelines by the Ordinance of the Minister of Health from the 23rd of December 2015 [14]. By 2015, to obtain a category A driving licence in Poland, a correct binocular vision had been required, although one could apply for a category B driving licence [18]. Colour vision for drivers in the UK is not required, which is consistent with the EU recommendations [6, 12, 13]. In Poland, this issue is diverse; car and motorcycle drivers do not have to distinguish between colours, but bus and lorry drivers must correctly recognise red, green and yellow [11]. This is in accordance with the Annexe III of Directive 2006/126/EC of the European Parliament and the Council from the 20th of December 2006 on driving licences. The above also mentions that the standards set by the Member States for the issue or any subsequent renewal of a driving licence may be stricter than those set out in this Annexe [13]. Mesopic vision, glare and contrast sensitivity are not required but may be ordered as an auxiliary examination for a person who is considered for a driving licence despite not meeting the visual acuity criteria according to the EU recommendations [13]. In Poland, they are required for bus and lorry drivers. However, for motorbike and car drivers they are not obligatory but are performed if the examined person has implanted intraocular lenses, is after refractive surgery, or for other reasons resulting from medical examination [11]. In the UK glare and contrast sensitivity or mesopic vision are not required. However, the plate test can be a substitute of glare or contrast sensitivity test especially in the case of cataract [19–21]. Required ophthalmological specifications are enough to drive. The analysis of road crashes in 2014 and 2018 shows that the number of collisions has been decreasing both in the entire EU, in particular Poland and the UK [22, 23]. Detailed results are collected in Table 5. While throughout that time the EU recommendations and ophthalmological guidelines applicable to drivers in the UK have not changed, in Poland they have become much more liberal after 2015. The 10% decrease in the number of road crashes in Poland is therefore not related to the relaxation of ophthalmic parameters for drivers but rather results from speed limit, road safety observatory, better road infrastructure, safer cars and greater road culture of drivers [24, 25, 26, 27]. In the period considered, the effect of road crashes i.e. the number of fatalities and injuries, also significantly decreased in Poland. Conclusions Current minimum vision requirements for drivers in Poland resulting from the Ordinance of the Minister of Health from the 30th of August 2019 (medical examination of applicants for driving licence and drivers) are closely integrated with the European Union recommendations expressed in the latest update to the Directive 2006/126/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on driving licence and are similar to the criteria in the United Kingdom. Similarities with minor nuances relate especially to visual acuity, visual field and binocular vision and differences occur in the approach to colour vision. A detailed analysis of road crashes in Poland, the United Kingdom and the European Union has shown that the visual requirements for drivers in these places are not too strict but sufficient to maintain safe driving. Moreover, the example of Poland shows that the liberalization of ophthalmic norms applicable to drivers does not lead to an increase in the number of road crashes. Thus, it is possible to further relax the ophthalmic standards for drivers.

References 1.Foley DJ, Heimovitz HK, Guralnik JM, Brock DB (2002): Driving life expectancy of a person aged 70 years and older in the United States. Am J Public health; 92(8):1284-1289. 2.Talbot A, Bruce I, Cunningham CJ et al (2005). Driving cessation in patients attending a memory clinic Age Ageing;34(4):363-368. 3.Desapriya E, Harjee R, Brubacher J, Chan H, Hewapathirane DS, Subzwari S, Pike I (2014): Vision screening of older drivers for preventing road traffic injuries and fatalities Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Feb 21;(2):CD006252. 4.Owsley C, Stalvey BT, Wells J, Sloane ME, McGwin G Jr (2001): Visual risk factors for crash involvement in older drivers with cataract. Arch Ophthalmol. Jun;119(6):881-7. 5.Stopyra W (2019): Czy prawo jazdy tylko dla osób z dobrym wzrokiem? Magazyn lekarza okulisty 13 (2): 95-100. 6.Rees GB (2015): Vision standards for driving: what ophthalmologist need to know. Eye volume 29, 719-720. 7.Bron A, Visvanathan A, Thelen U, Natale R, Ferreras A, Gungaard J, Schwartz G, Buchholz P (2010): International vision requirements for driver licensing and disability pensions: using a milestone approach in characterization of progressive eye disease. Clin Ophthalmol. 2010 Nov 23;4:1361-9 8.Mérour A, Favrat B, Borruat FX, Pasche C (2014): Requirements on the vision for driving: to see more clearly. Rev Med Suisse. Nov 26;10(452):2252-4. 9.Wilhelm H (2011): Vision and car driving ability. Ther Umsch. May; 68(5):243-7. 10.Vision Requirements for Driving Safety with Emphasis on Individual Assessment Report prepared for International Council of Ophthalmology. www.icoph.org 11.Ordinance of the Minister of Health of August 30th 2019 on medical examinations of applicants for driving licences and drivers. Law Journal of 2019, item 1659 12.Visual disorders assessing fitness to drive. www.gov.uk 13.Directive 2006/126/EC of the European Parlament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on driving licence. Official Journal of the European Union. Document 02006L0126-20180722 14.Ordinance of the Minister of Health of December 23rd 2015 changing Ordinance on medical examinations of applicants for driving licences and drivers. Law Journal of 2015, item 2247 15.Stopyra W (2019): Orzecznictwo okulistyczne. Wydanie 4. Górnicki Wydawnictwo Medyczne Wrocław : 1-357 16.Directive 2002/24/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 March 2002 relating to the type-approval of two or three-wheel motor vehicles. Official Journal of the European Union Document 32002L0024 17.Latham K, Katsou MF, Rae S (2015): Advising patients on visual fitness to drive: implications of revised DVLA regulations. Br J Ophthalmol. Apr;99(4):545-8. 18.Stopyra W (2013): Wybrane zagadnienia z orzecznictwa w okulistyce – program edukacyjny Kompendium Okulistyki, Okulistyka 1’ (21):1-24 19.Rae S, Latham K, Katsou MF (2016): Meeting the UK driving vision standards with reduced contrast sensitivity. Eye (Lond). Jan;30(1):89-94. 20.Swan G, Shahin M, Albert J, Herrmann J, Bowers AR (2019): The effects of simulated acuity and contrast sensitivity impairments on detection of pedestrian hazards in driving simulator. Transp Res Part F Traffic Psychol Behav. Jul;64:213-226. 21.Fraser ML, Meuleners LB, Lee AH, Nq JQ, Morlet N (2013): Which visual measures affect change in driving difficulty after first eye cataract surgery? Accid Anal Prev. Sep;58:10-4. 22.Symon E (2016): Wypadki drogowe w Polsce w 2015 roku. Komenda Główna Policji, Warszawa; 1-86 23.Symon E (2020): Wypadki drogowe w Polsce w 2019 roku. Komenda Główna Policji, Warszawa; 1-85 24.Abounoas, Z., Raphael, W., Badr, Y., Faddoul, R., Guillaume, A. (2020). Crash data reporting systems in fourteen Arab countries: challenges and improvement. Archives of Transport. 56(4), 73-88. 25.Gaca S, Pogodzińska S (2017): Speed management as a measure to improve road safety on Polish regional roads. Archives of Transport. 43(3), 29-42. 26.Żukowska J (2015): Regional implementation of a road safety observatory in Poland. Archives of Transport. 36(4), 77-85. 27.Wang, P., Gao, S., Li, L., Cheng, S., Zhao, H. (2020). Research on driving behavior decision making system of autonomous driving vehicle based on benefit evaluation model. Archives of Transport. 53(1), 21-36.

Conflict of interest: No conflict of interest. Financial Disclosure: No author has a financial or proprietary interest in any material or method mentioned.

|